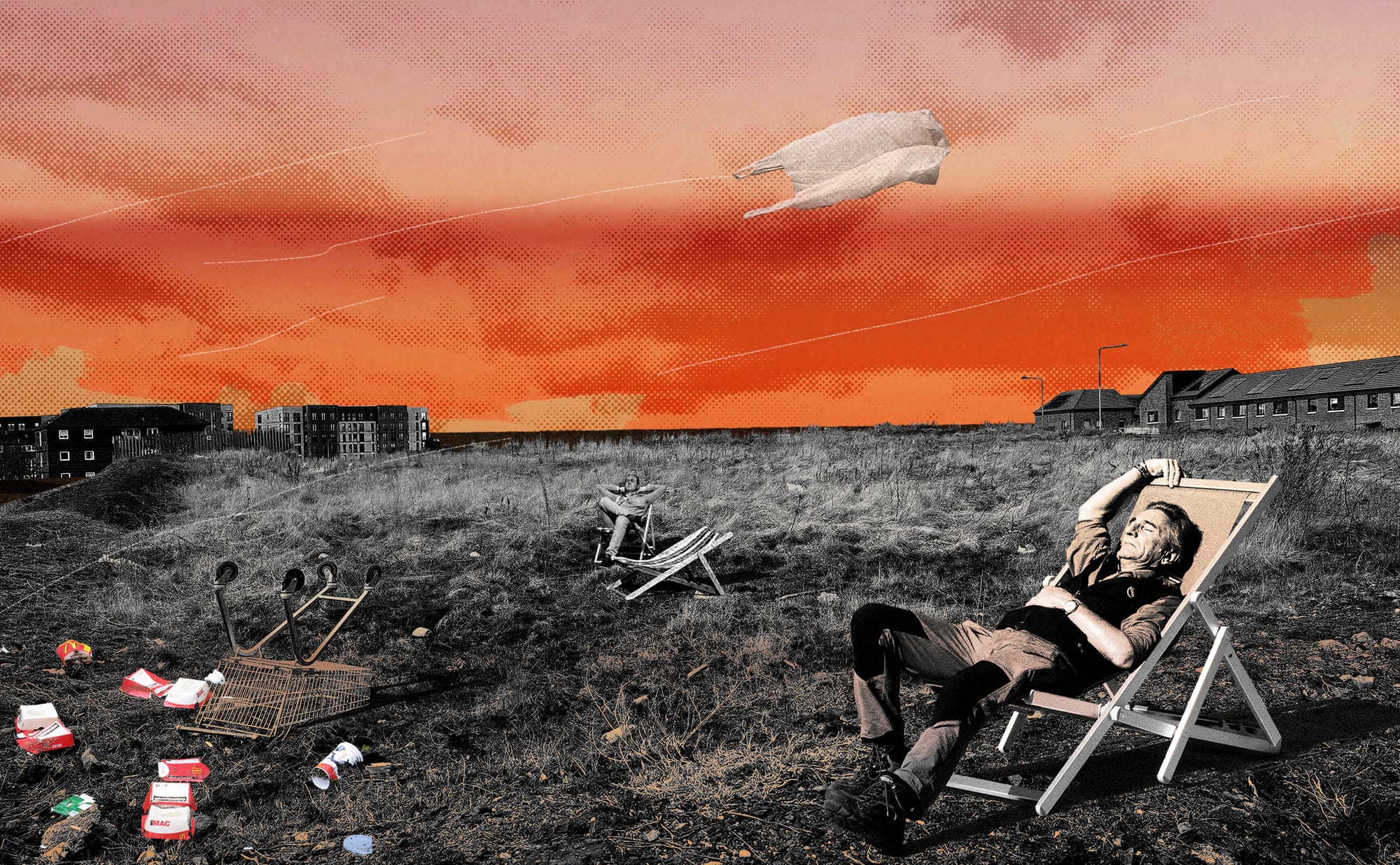

A couple of days before I’m due in Dalmarnock to meet local residents, my phone pings. “Some arsehole has dumped a bath,” the text says. “A fucking bath.” It is the latest addition to a fly-tipping pile at the entrance to Glasgow’s great regeneration dream. Like many in the neighbourhood, this resident has had enough. “I’ve cracked,” they tell me. “I’m emailing our councillors today.”

Not so long ago, few people would have batted an eyelid at rubbish being dumped on this particular site. A post-industrial wasteland partially encircled by a loop in the River Clyde, it had been left barren and contaminated when the dye factories, print works and paper mills it once housed shut down. Much of the community those factories supported had moved on too, shipped out to peripheral housing estates in the clearances of the 1960s. Largely forgotten in recent times, if the area was remembered at all, it was as an east end outpost of deprivation.

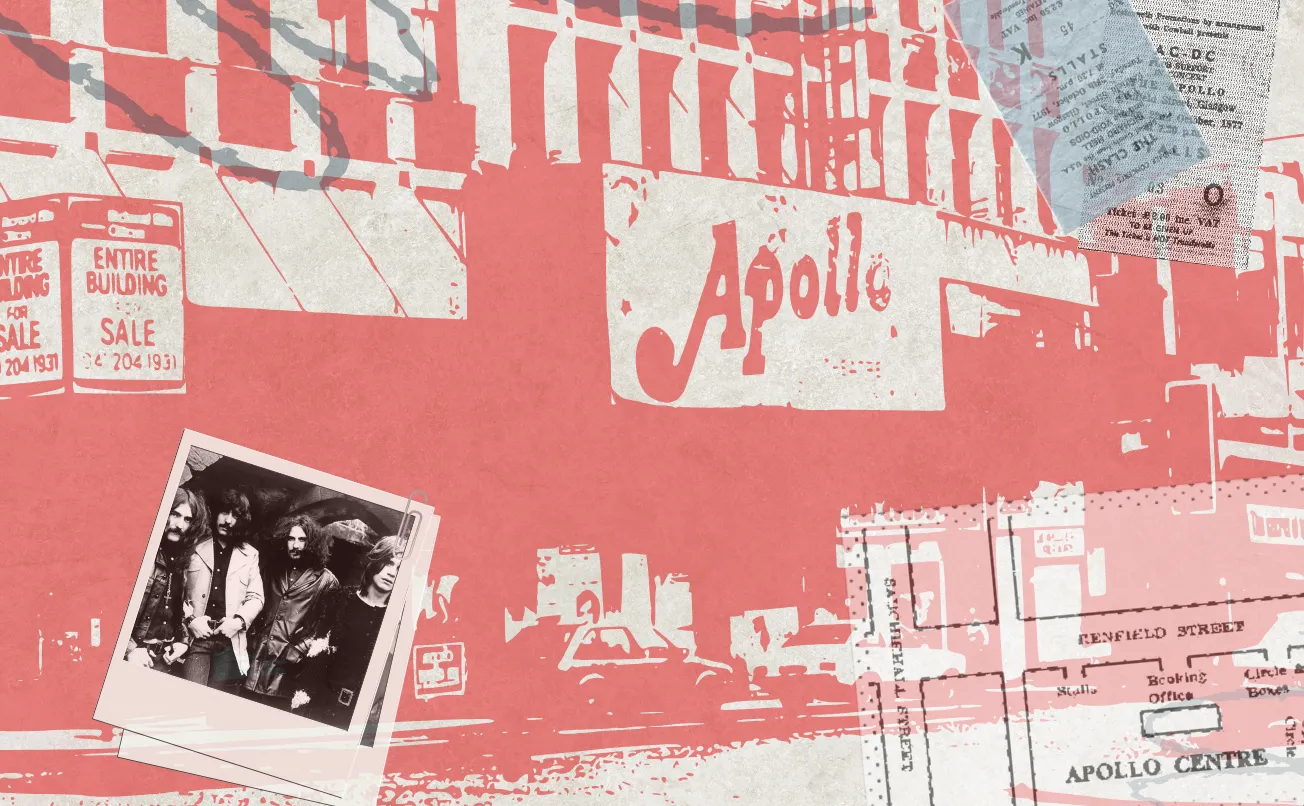

Then Glasgow won the bid to host the 2014 Commonwealth Games. A velodrome, sports arena and athletes’ village had to be built and, with so much land available, all eyes turned to Dalmarnock.

The athletes’ village was a particular triumph. Master-minded by renowned architects Paul Stallan and Alistair Brand, it was designed, as they put it at the time, to be “an urban regeneration and planning exemplar on every front”. When the games were over, the beautifully imagined buildings were turned into 700 homes, 400 to be managed by housing associations, 300 for private sale. Great swathes of neighbouring land have been transformed since. Infrastructure remains patchy — promised amenities such as a Lidl supermarket yet to materialise — but hundreds of new homes across multiple developments have been created, and the still-gleaming Riverbank Primary School has been operational since 2019.

One long, thin strip of land has very conspicuously been left out of the action. Nestled between the 2014 village and Dalmarnock Road, the Athletes’ Village Phase Two should have been built and occupied long ago. Planning approval for that portion of the site, designed by Stallan-Brand alumnus Stewart Stevenson, has been granted twice since 2017, but work has yet to begin. Wider regeneration of the area has gradually reduced the number of sites that attract fly-tippers. Instead they have convened on the gateway to the original village, which is now a dumping ground. For those living there, it leaves a bitter taste.

Eileen Smillie and Stephen Thomas were among the first to buy houses in the 2014 village. The former, a retired biomedical scientist, was convinced to swap the family home in Pollokshields for a Stallan-Brand townhouse after her husband — employed on the site during the construction phase — infected her with his enthusiasm. Thomas, meanwhile, had worked at Stallan and Brand’s former firm, RMJM, while their master plan was being drawn up. Recognising how significant it was going to be for the east end, he wanted to be part of it.

As we stroll from the neatly kept village to its rubbish-strewn sister site, the pair, both members of the village residents’ group, tell me they are as enthused about their homes and the area as they ever were. It’s just that, with Glasgow gearing up to host another Commonwealth Games next year — a pared-back version; no athletes’ village is being provided — their frustrations that the promised legacy of the 2014 edition has not been fulfilled have been exacerbated.

“Lots of really nice housing has popped up all over Dalmarnock,” Thomas says, “but this is the last bit of the jigsaw.” Smillie agrees, saying that after a decade in their homes, and with a second Games just around the corner, local residents are now “sick” of waiting for phase two to materialise.

It’s not just that the lack of development is unsightly — the fly-tipping is causing a danger to public health too.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.