He remembers it all. The old, pallid building looming over Renfield Street like some sort of monolith. The characters queued up outside, full of angst, Buckfast and anticipation. The sweaty, gritty feel of the place. The bouncing balcony. Most importantly, he remembers the wild, deafening thrashing of guitars, the thudding drums, and the booming vocals of the mythological metalhead heroes on the stage – “twelve feet tall, not ten,” as he insists – before him.

It wasn’t an idea born of love for the venue, but instead one of “getting pished with friends” and reminiscing about the shows they remember going to. Since 2002, Scott McArthur and friend Andy Muir have documented the performance dates, setlists, and anecdotes (with the help of nostalgic visitors) attached to the storied music venue, the Apollo Theatre, on the charmingly archaic, Teletext-esque Glasgow Apollo website.

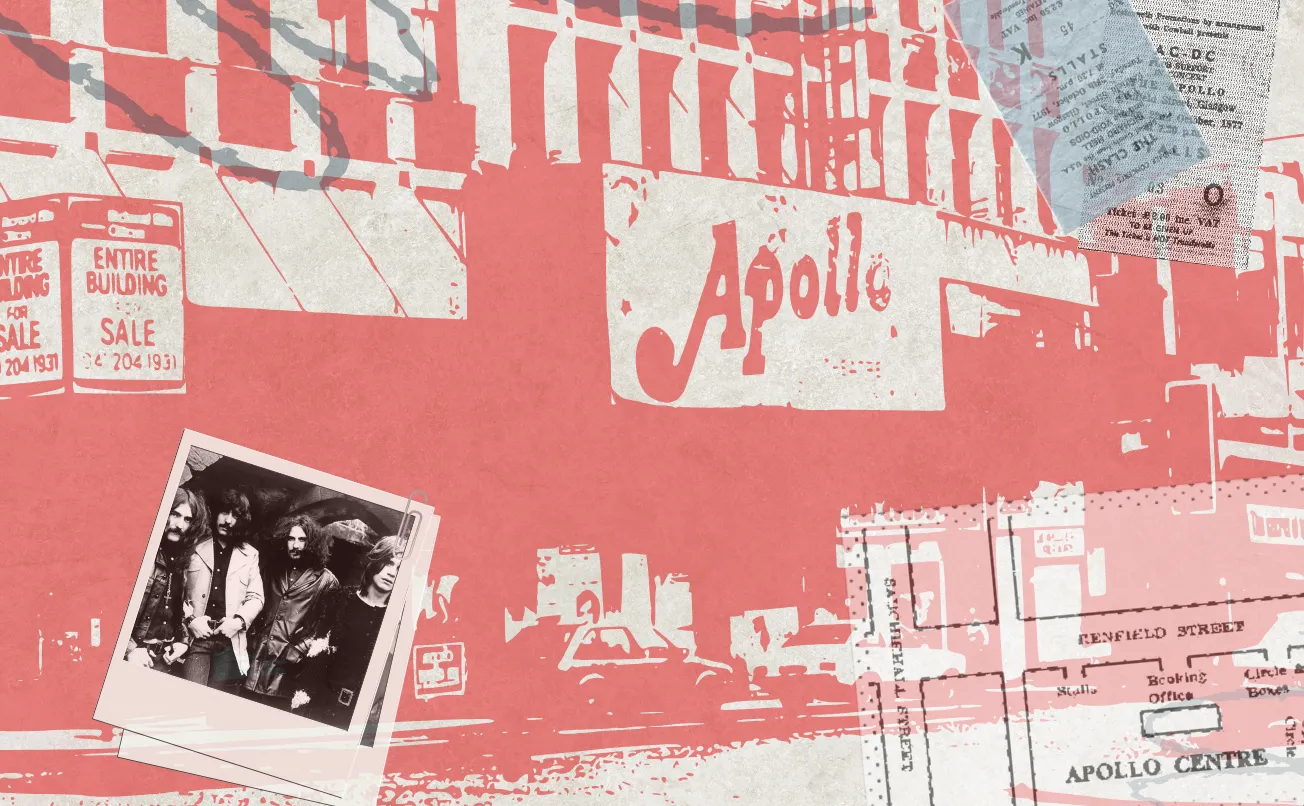

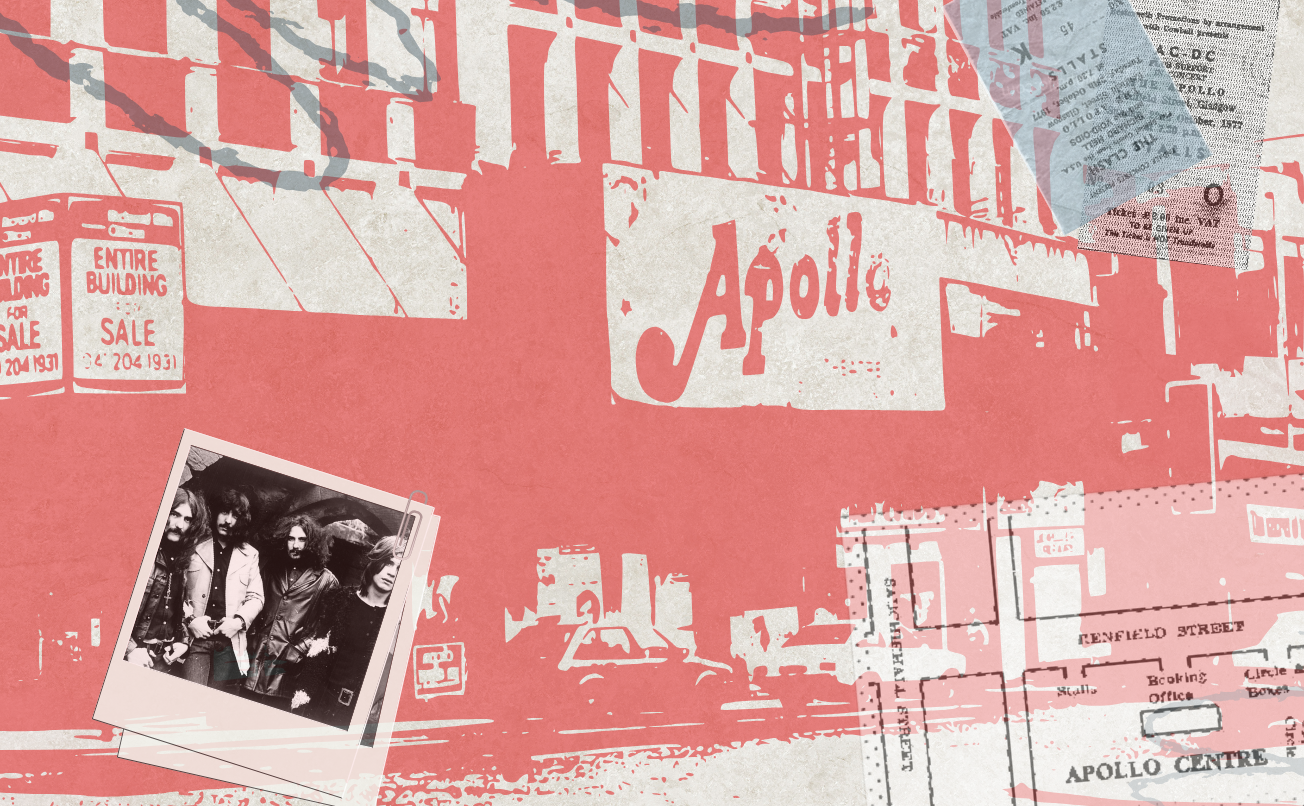

In the 40 years since the curtains finally closed on the Apollo — Scotland’s ‘premier rock venue’ between 1973 and 1985 — a huge digital archiving effort, dedicated to preserving the venue’s legacy, has emerged. Thousands of members (McArthur calls them the “Apollo Choir”), now in their late 50s and older and scattered across the globe, congregate in a Facebook group also moderated by McArthur and Muir. Here, they discuss their fondest memories of Glasgow’s “fungus-encrusted dump.” Others keep the Apollo alive by taking home parts of the building itself, constructing 3D models of the theatre and writing rock musicals about the fans who frequented it.

But why does the Apollo loom so large in not just Glasgow’s memory, but Scott McArthur’s?

Live at ‘The Appalling’

For McArthur — then a self-confessed “little geek” from Lanark — it all began with a copy of the hard rock compilation album Axe Attack, which included songs from the likes of Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, and Motörhead. “That album was like the Bible for us kids on the playground,” McArthur laughs. “I can still probably name every song on it, in order. It just became such an important thing in my life.”

In November of 1981, McArthur would see his first gig (of many) at the Apollo: English heavy metal band Judas Priest were playing, supported by German metal band Accept, on their World Wide Blitz Tour. “When the guitarists – K. K. Downing and Glenn Tipton, I think – started playing, I just remember thinking to myself: ‘what the fuck is this!’ It was just ridiculous. I had no idea what to expect,” McArthur recalls. “Up on that stage, they were like mythical creatures.”

The building itself held a huge amount of mythos for McArthur too. 126 Renfield Street’s first incarnation as Green’s Playhouse — an entertainment complex opened in 1927, complete with a cinema with a record-breaking seating capacity of 4,368, a ballroom, and a tea room — was commissioned by cinema pioneer George Green and designed by local architect John Fairweather. In 1973, with the approval of Green, the Playhouse was taken over by Frank Lynch and Max Langdown of Unicorn Leisure and transformed into the Apollo, named after the iconic Harlem venue. American star Johnny Cash christened the newly-rebranded Apollo, as its first headliner in September 1973.

By the time McArthur was coming of age, the Apollo had garnered a reputation as a decaying hub of filth, foul odours, and riotous fun, eventually earning the nickname ‘The Appalling’ amongst its loyal patrons and scandalised detractors — typically concerned parents of the former — alike.

“For a working-class kid from Lanarkshire, the Apollo itself was sort of like a myth,” he says. “Going into Glasgow on the train was already a big deal, but that building… it was huge. It was almost like a living creature.”

There was a freedom to the Apollo, according to McArthur. “Hundreds” of Glasgow youths went to hang out there. “Frank Lynch, the guy who ran the place, wasn’t interested in money, and wasn’t bothered about security at all, really. You could just come into the building and wander around. We used to meet there and just chat, or hang out and talk to girls. It was a grimy old dump by the 1980s, but it really was the place to be.”

In his book Big Noise: The Sound of Scotland, writer Martin Kielty claims that the Apollo was also regarded as the place to play by several musicians. In its 12-year run, almost all of the largest rock acts of the era graced the 12-foot-tall stage. Bands from Blondie to Black Sabbath played to rowdy crowds, returning several times to the “grimy old dump” just to hear the roars of the Glasgow Choir.

Escape from the downturn

The heyday of the Apollo coincided with some of the bleaker chapters in recent Glaswegian history. The 1970s saw a record-high number of industrial disputes in the United Kingdom across multiple sectors, and Glasgow was no exception to this. In 1975, dustcart drivers went on strike as a means of protesting their low wages. As a result of this, 50,000 tons of rubbish began to pile up in the streets of the city, creating a major health hazard for residents.

Unemployment in Scotland doubled in the second half of the 1970s, and again in the first half of the 1980s. At the same time, widespread deindustrialisation under Margaret Thatcher’s prime ministership affected not only employment rates, but mortality outcomes and social wellbeing in Glasgow.

This mass unemployment as a result of deindustrialisation left many heavy industry workers dealing with mental illness, isolation and poverty, often turning to alcohol and drugs as a form of consolation.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, with the high levels of unemployment, when you were in school you were told to just get your O-Levels and get out of Glasgow. There was just a general sense of hopelessness in the city at the time,” says Niall Murphy, director of Glasgow City Heritage Trust.

But for some kids coming of age amid the downturn, escape could be found in music.

“It was a very dark time,” muses McArthur, his tone becoming momentarily sombre. “When you were skint, and I was — my family had no money at all — the music just gave you something to look forward to. I remember listening to my crackly records in my bedroom… they were like a light amidst all the darkness.”

The affordable prices of tickets to gigs at the Apollo helped to cement its place in the hearts of working-class music fans. It would cost you only £1.00 (roughly £7.59 in 2025) to see Scottish pop-act-turned-phenomenon The Bay City Rollers perform at the Apollo in 1975, at what was arguably the peak of their career. To put this in perspective, general sale tickets for pop superstar Sabrina Carpenter’s recent gig at Glasgow’s OVO Hydro were said to range from £58.45 to £115.20.

As well as making live music accessible to working-class audiences, the Apollo also gave working-class performers their moment in the spotlight. Beloved by rebellious youth, loathed by concerned parents, and virtually unknown south of the Scottish border, Easterhouse-based rock band Scheme found exceptional success in the local music scene. In what remains to be one of the most impressive feats in local music history, Scheme played a packed-out gig in the Apollo, despite having no recording contract, in September of 1984.

“You’d almost exclusively find out about gigs through word of mouth. With Scheme, for example, it was incredible. They sold the Apollo out, and they weren’t even signed to a record label. They didn’t even release music or anything!” McArthur exclaims. “That’s like an unsigned band selling out the Hydro now.”

The Apollo, in a sense, served as a mecca for disillusioned working-class Glaswegian youth. The “tribes”, as McArthur calls them, of punks, goths, rockers, mods, and various other subcultures now lost to time, allowed young working-class Scots to forge an identity for themselves, in a socioeconomic landscape wherein they were becoming increasingly isolated and powerless.

“It’s cliché, but at the time there really was a sense of community within the Apollo, and in the local music scene overall,” he continues. “On one side of the road you’d have Clash fans lining up outside the Apollo, and on the other, you’d have Cure fans going into the Pavillion. You’d both be throwing abuse at each other, but there was never really any violence — it was more like witty banter, with a few choice words here and there. It was all just good fun.”

Derek McAdam, former owner of an independent record store in Ayr and “all-star contributor” on the Apollo Facebook group agrees. “So many friendships and relationships came out of attending gigs at the venue,” he adds. “It really was the heart of a great music scene in Glasgow.”

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. In 1978, the venue risked being turned into a bingo hall through a takeover by Mecca Ltd, only to be saved by a petition started by two 15-year-old Apollo fanatics, which ended up accumulating almost 100,000 signatures, according to Kielty’s Big Noise.

Ultimately, what was arguably the filthy, beating heart of the Glasgow music scene quietly stopped in the summer of 1985, with one last concert in June, by The Style Council. It was lost forever between 1987 and 1998, when the building was first demolished after being declared unsafe, and then destroyed by a fire. The Apollo had lost a long battle against rising running costs, a changing music landscape, and a building increasingly suffering from burst pipes and decaying infrastructure.

Today, 126 Renfield Street is almost unrecognisable. A 12-storey, post-modern style cinema was eventually erected on the site, first opening in September 2001 as part of the UGC chain (later sold to Cineworld in 2004). Like Green’s 1920s Playhouse, Cineworld Glasgow is similarly record-breaking — it was entered into the Guinness Book of World Records in 2000 as the world’s tallest cinema.

Unlike its predecessor, however, the Cineworld was initially met with contempt from the local community upon construction. In 2000, the building was awarded the less-than-honourable title of Carbuncle of the Year, with internet users voting in an online poll by architectural magazine Prospect seeking to find Scotland’s ugliest building.

Although many are somewhat pessimistic about the current existence (or lack thereof) of a successor to the Apollo at its peak, McArthur — a champion of embracing the modern world and technology — remains hopeful. “In all honesty, for kids now, I think the closest thing to it is gaming. You can build similar communities, plus it’s cheaper, and you can do it at home.”

For thousands of aging rockers, punks, goths and the like, however, that community feeling lives on in McArthur and Muir’s Facebook group. Members share their favourite memories of gigs, photos of ticket stubs, and discuss the artists who graced the famous twelve-foot-tall stage almost daily, while regular shows (which McArthur himself describes as “basically just piss-ups!”) featuring discussions of the Apollo and music from some of the venue’s most memorable performers are live streamed on Friday nights, followed by a Zoom call.

These started in lockdown, says McArthur, and have become a new point of connection. We’ve had people meet, reunite with old friends, we’ve even had marriages happen as a result of the Zoom calls!” he exclaims. “I’ve had guys message me on here, saying things like ‘your group saved my life, Scott’ — it’s just so strange.”

And he’s come to a conclusion. “At the end of the day, the bands never really mattered. They were just pop acts. They were transient, they’d come and go. It was the fans — the Apollo Choir — who were important, and whose spirit lives on.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.