Sitting in the back of my dad’s car as a kid, I would crane my neck to glimpse the tops of Glasgow’s looming tower blocks: the blue and red of Cedar Court’s side elevation shooting skywards; the totemic Anniesland Court rising out of a concrete tangle of roads; Knightswood’s five towers spotted from a distance. Having spent my very early years in a tenement in Langside, these towering monoliths were foreign and fascinating: unknowable, vast, impossibly tall. The vertiginous height of Anniesland Court, all 22 storeys, was dizzying compared with my grandparents’ semi-detached home just along the way on Anniesland Road. I didn’t yet have the words to describe these buildings, but I already had ambivalent feelings about them.

Brutalism has been on a journey in recent years. “Brutalism Is Back,” read an article in the New York Times in 2016. “Instagram's in love with bare-faced brutalism,” reported the Guardian in 2018. “Love it or hate it, Brutalist architecture has a place in the 21st century,” volleyed the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation last month. Not all headlines have been as forgiving. “Demented post-war planners brutalised Britain with their concrete monstrosities. Demolish them,” urged the Telegraph only five years ago. Two years ago, The Herald asked “Can we learn to love Glasgow's 'ugliest' buildings?”.

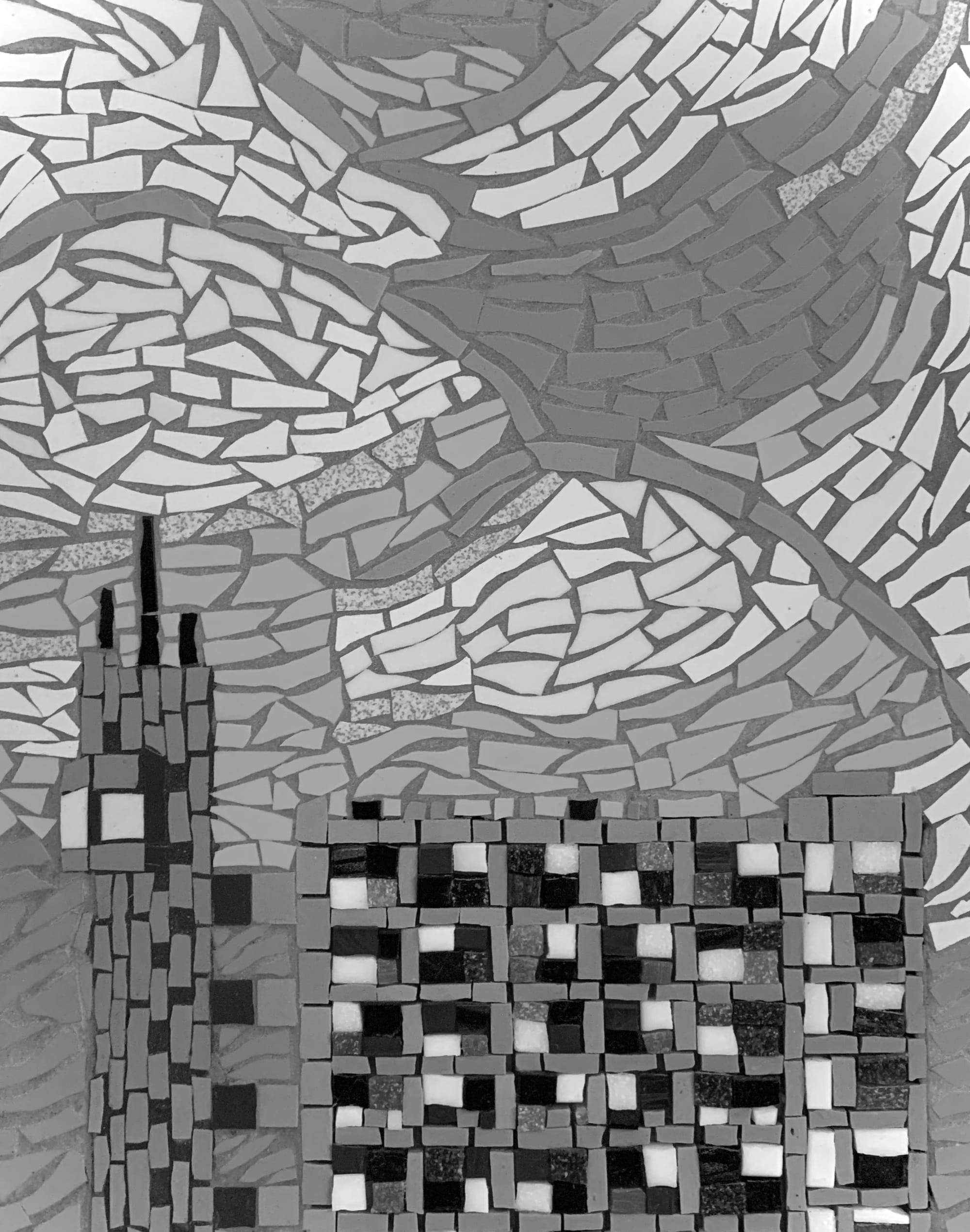

Recently, visiting a friend’s family home in London, I noticed a mosaic of Trellick Tower, Ernő Goldfinger’s Kensal Town high-rise, on the wall. Its presence seemed to represent the public’s shift in perception towards Brutalism. It also spoke of the contrast in how a certain type of Londoner has come to view their city’s Brutalist structures, compared to how Glaswegians view their own. Rather than a gift shop kitschification of Brutalism, this was an artwork handmade by a family member, a tribute to the ideals of postwar social housing. Like the Brutalist building itself, it looked perfect in its imperfections, at ease with its raw materials.

The house I was sitting in, as it happened, was on Thompson Avenue, named after William Thompson, my friend’s dad explained, the man behind London’s first council housing project. Known as the ‘Richmond Experiment’, the modest row of terraced houses on Manor Grove in North Sheen, completed in 1895, was a testament to the pioneering vision of Richmond’s ‘People’s Champion’, a rethinking of the state’s responsibility to provide adequate housing for its burgeoning inner-city populations.

Sitting down at the table, the idea of a similarly middle-class family in Newton Mearns having a framed picture of the Gallowgate Twins on their wall struck me as improbable. Or at least it did until a recent exhibition urged Glaswegians to reassess their relationship with the city’s concrete buildings.

‘Brutal Glasgow,’ devised by curator Rachel Loughran, and featuring the artwork of illustrator Natalie Tweedie (who goes by the moniker Nebo Peklo), explores the city’s love-hate relationship with Brutalism. It features first-hand accounts from people who lived and worked in Glasgow’s Brutalist buildings. The exhibition itself is deceptively simple: eight of Tweedie’s textile-inspired works from a series of Brutalist illustrations she made in 2023, framed and mounted on a wall.

However, scan any of the QR codes next to each work, or visit the online exhibition, and you’re quickly immersed in a world of rich multimedia, from archival imagery and photography from 1957 to the present day, to oral histories and essays by architects, academics and writers. The exhibit takes as its parameters Natalie’s eight different buildings (not all of them strictly Brutalist): the Bluevale & Whitevale towers, better known as the Gallowgate Twins; Our Lady and Saint Francis; the College of Building and Printing; the Savoy; the BOAC; the Pontecorvo; the Bourdon; and Anniesland Court.

If you're reading this and you haven't yet joined our free mailing list, click here to get Glasgow's new quality newspaper in your inbox every week.

Emblazoned with the hot pink ‘People Make Glasgow’ sign, but currently vacant and in a state of limbo since a £60m development plan fell through earlier this year, the College of Building and Printing earned the unenviable distinction of being named as one of the ugliest buildings in the UK last year, albeit in a list compiled by the photography website Parrot Print. Responding to the news on Twitter, Tweedie posted what is now her well-loved drawing of the building, along with the caption: “proves that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

This week voted the 2nd ugliest building in the UK proves that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The former College of Building and Printing (or the ‘People Make Glasgow’ building for the youth). Available as a print on my website (link in bio) #Glasgow #brutalist pic.twitter.com/R3i4F7pD5z

— Natalie (@nebopeklo) March 23, 2023

Before embarking on her Brutalist series, Tweedie asked herself why we celebrate Victorian buildings, but can’t celebrate these buildings too. “It was my attempt to make something beautiful out of things other people would consider ugly,” she says, her feet barely back under the desk following a honeymoon in Berlin, where, quite naturally, she visited Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, the pioneering Swiss architect’s modernist residential housing typology.

When Tweedie moved out of her childhood home, her first flat was in the Tarfside Oval estate, in one of the four tower blocks which stood 22 storeys tall in Mosspark. The high-rises were demolished in 2015 and 2016 and have now been replaced with 51 new homes. “It was a very safe community,” she says.

“It’s a generational thing. A lot of older people hate these buildings, but you've got to remember why they were built in the first place. Contrast it with what’s happened in London. The Barbican, Trellick Tower, flats selling for millions – it just didn’t work here,” Natalie adds.

Two of the buildings rendered in Natalie’s representational style in ‘Brutal Glasgow’, the Gallowgate Twins and the Pontecorvo, were demolished in 2014 and 2021 respectively, part of her motivation for documenting them in the first place.

“Whether you love or you hate these buildings, whether you lived in the tower blocks, or whether you had to look at the Gallowgate Twins and hated their presence, I think it's important to capture these buildings which are no longer here.”

Bluetooth headphones on, staring at Tweedie’s playful depiction of the Gallowgate Twins and scrolling through the digital exhibition, I am met with black-and-white pictures of ’60s Glasgow, the twin towers blocking out the sky behind Camlachie’s tenement rows. Scroll again, and there’s a sudden cut to colour. Another swipe, and the Twins are reduced to rubble.

While Glasgow’s Brutalist, high-rise story is far from unique, it is particular. The city experienced the most concentrated multi-storey drive of any city in the entirety of Britain, with three times as many high-rise tower blocks (defined as 20 storeys or higher) as London, and 18 times more than Birmingham. Having seen as many as 230 high-rises rise, and a great many of them subsequently fall, it’s little wonder that Brutalism and tower blocks are intertwined in the Glaswegian imagination. Part of the exhibition’s section on the Gallowgate Twins features an excerpt from Chris Leslie’s Lights Out, a documentary from his “Disappearing Glasgow” project, featuring interviews with the first and last residents of Bluevale and Whitevale.

“Maybe Glasgow is realising – or the people who built these things – that some of these high-rise flats were a mistake. A good idea principally, but there was no long-term thinking. You can’t make people live together like that,” the former resident tells the viewer.

The rich archival research behind each of the illustrations is the work of the exhibition’s curator, Rachel Loughran, who specialises in digital design. “I do think that a building is much more than its material, especially in a material as controversial as concrete. What is concrete to many people? It's ugly, it's grey, it stains, it's associated with public housing that has been denigrated across the media for the past 40 years or however long,” Loughran tells me over the phone.

“But within those bricks, within that structure, people have had everyday experiences, and they think about it completely differently to somebody who has just come across a shape in the sky. So I think it's important to bring some of those stories in, because they … give a life to the building that, unless it's recorded, unless it's documented, disappears with the building,” she adds.

“I wonder if most Glaswegians . . . think about Brutalism and think of the high-rise towers and not a more general reflection on Brutalism as being a wider architectural movement. They don't think of the National Theatre or the Barbican Centre or Coventry Cathedral,” Loughran posits, before adding that the latter was designed by Basil Spence, the architect behind Queen Elizabeth Square in the Gorbals. Spence’s ambitious housing experiment ended its life as an emblem for poor planning and social deprivation, tarnishing the Scottish architect’s career. It was demolished in 1993, killing a mother of four, Helen Tinney, in the process. (Its final days and demolition were poignantly documented in the BBC documentary High Rise and Fall.)

“I think a lot of Glaswegians think: ‘Brutalism. Gorbals. They failed. Basil Spence’s designs were terrible.’ … If they know these stories, then you can understand that these are almost antagonistic buildings,” Loughran says.

When I was studying at Glasgow University, the Brutalist campus failed to make my heart soar, the greys of the Adam Smith and Rankine buildings often matching my mood. Over the years, I watched as the hulking masses of the Boyd Orr and the library were cladded over, as if the modesty of their raw concrete needed to be covered up in response to changing mores. Officially, the reason given was to “improve insulation and extend lifespan” of the buildings – concrete and dampness being bedfellows. Many of the campus’ Brutalist buildings still stand uncladded, monuments to utopian visions of the past. For how much longer, I wonder.

In my mid-twenties, my feelings about Modernist and Brutalist-inspired architecture began to soften. By my late twenties, I’d dragged my friends along to Le Corbusier’s original Unité d’habitation in Marseille, the building that birthed Brutalist architecture itself. Standing underneath what felt like a berthed cruise liner, albeit a beautiful concrete one, I struggled to reconcile the simplistic beauty with its hostile underbelly. I was as amazed by the collectivist, utopian philosophy underpinning the simple form and function of the building as I was by the stories of damp, structural problems and difficulties with lighting and ventilation. Much like Mackintosh’s Hill House, it seemed to prove a building could be flawed and perfect at the same time. Back in Glasgow, I saw Glasgow’s most divisive buildings with fresh eyes, such as the College of Building and Printing – jutting out of North Hanover Street and shifting its shape according to your perspective and position on the city’s grid. Glasgow’s BOAC building began to pop, its folded sheets of copper and futuristic figure confidently taking up space on Buchanan Street.

“[High-rises are] a reminder of an era in which there was huge upheaval. … It was a real belief in the future, and a real belief that technology would solve our problems. Unfortunately … great leaps forward are always really risky and don't necessarily work out, or can have unintended side effects,” explains Niall Murphy, director of Glasgow City Heritage Trust, which is hosting the exhibition at their Bell Street offices. He’s well dressed, with a white beard and thick black glasses, and makes us a pot of coffee before sitting down to chat.

“[Brutalism is] more pronounced in Glasgow … When you look at the combination of the comprehensive development areas, plus the kind of radicalism of the new estates that were being put up, but also the weirdness of some of the locations of new estates, which don't really make sense – the same kind of organic sense of a neighbourhood, in the sense of belonging to a neighbourhood, is very much shattered in Glasgow in a way that doesn't happen with any of the other Scottish cities,” Murphy explains.

“Even when you look at Liverpool and Manchester and Birmingham, everything Glasgow does is bigger, more radical,” he adds.

After visiting the exhibition, I cycle over to Our Lady and Saint Francis, perhaps not technically Brutalist but certainly Modernist (the exhibition doesn’t split hairs therein). It’s an arresting building, one which has stopped me in my tracks many times before, dissimilar to the old and new architecture it sits alongside on Glasgow Green. The close attention I’m paying to the former school causes passers-by to follow my eyeline to Our Lady, before looking back at me askance, confused as to why I am concerning myself with this grey-brown building.

Nick Durie lives in Maryhill's Wyndford Estate, on the same street as one of the four towers. He moved here to raise his family in 2012. The 600-odd homes available for social rent sit proudly above the bosky River Kelvin and have done so since they were built by Ernest Buteux between 1961 and 1969. “Anyone who’s seen the Barbican knows there’s nothing inherently or intrinsically wrong with Brutalist architecture, it just requires sensitive treatment,” Durie argues. In the mid-noughties, Durie lived on the 17th and 18th floors of Woodside’s Cedar Court. Before moving in, he’d been homeless, and spent a few weeks in a hostel.

“Having my own home instead of a bedsit was hugely beneficial to me. On a sunny day I could see Ben Lomond, with panoramic views of the city,” he tells me nostalgically. He explains how the residents had to fight to save the estate and stop the land beneath being sold off for private development. In the run-up to COP26, the buildings were retrofitted to improve their energy efficiency and lifespan, in a project costing £13m.

“That’s the one tension I have with Brutalism, as preserved in aspic, because people have a right to have an energy-efficient home, and no one was building homes like that then,” he says. “You can’t heat your home with concrete. Cedar Court has mechanical heat recovery, it’s warm all the time and triple-glazed, people never need to heat their homes.”

He explains the history of the Wyndford estate, built as a critique of the engineer-led design of the Harold McMillan era, in which as much housing as possible was built as quickly as possible.

“They’d throw up [a building] without considering where the wind passes through, where people congregate. Then that leads to the demolition of Sighthill, which was a disgrace – but it wasn’t a great scheme.”

Sighthill, along with the Red Road Flats, was originally conceived as the answer to the city’s urgent need for social housing – allowing for the clearance of some of Europe’s worst slums, but eventually coming to typify poorly-designed high-rise living. The Red Road Flats were the tallest residential buildings in Europe when first built in the late ’60s, and were almost demolished as part of the 2014 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony. Public outcry put a stop to those plans, but they were eventually demolished in 2015, followed by the last of the Sighthill flats in 2016.

Much to Durie’s dismay, the Wyndford Towers are also facing the fate of the wrecking ball. The decision is deeply unpopular with the Wyndford Residents’ Union that Durie represents – so much so that they staged a sit-in last year, and have steadfastly opposed the demolition plans put forward by Wheatley, Scotland’s biggest housing association. Glasgow City Council and Wheatley have been on something of a demolition drive in recent decades, knocking down 30% of Glasgow's tower blocks ince 2006.

A week later, I’m five miles southeast of the Wyndford, standing in the shadow of 305 and 341 Caledonia Road. The 24 storeys of the two Gorbals towers cast a long shadow, glimmering in the afternoon sunshine. There’s fencing around the site, and decladding has already begun on one of the towers in preparation for their demolition. I wander around the perimeter, speaking to a few locals about the flats. A smiling elderly woman who has lived in the Gorbals for all of her 83 years stops to chat. Between gasps from a voice prosthesis, she tells me how popular the flats were among the residents, as does another woman walking her two dogs, who’s lived in a modern apartment overlooked by the towers for the past decade.

Along the road, I stop at a nondescript pub next to a Chinese takeaway. Towards the Clyde, Strathclyde distillery puffs white clouds of steam into the sky, and just out of sight are the four towers of Commercial and Waddell Court. Mags, who’s lived in the Gorbals her entire life, is sitting at the bar at the Pig and Whistle, the pub where her dad used to drink. She’s sipping on a Cointreau and diet Irn-Bru, and recounting all the high-rises she’s lived in over the past six decades. First, Queen Elizabeth Square, then the Caledonia Road flats after she got married, followed by Commercial Court.

Her voice is animated as she recounts her time in Queen Elizabeth Square: its shopping precinct and bars on the ground floor, the short-lived water feature between the blocks that kids loved to play in. She remembers the day the Queen came to open the flats, by which point her family had already moved in. She still has a picture with her and her brother and a few friends at the bottom of the 20-storey blocks, mini flags in hand, ready to wave at Her Majesty.

“My brother's holding a Union Jack right, but they’re all Celtic supporters, and my brother once went: ‘I've never held a Union Jack in my life’, and my sister got the photo out and says: ‘Well there you are there, holding a wee Union Jack’,” Mags says, breaking into a hearty laugh.

“We were fine, every one of the flats was fine. Everybody thinks it was like deprivation, but it wasn't. It was just like a big village.”

Brutal Glasgow is open Wednesday–Friday until 25 October, plus weekend opening 26–27 October. 10am – 4pm at Glasgow City Heritage Trust, 54 Bell Street, Glasgow, G1 1LQ. Free entry.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.