It’s just before 10pm and the Barrowlands is packed, stage lights turning the ceiling’s stars blue and red. Rising synth chords ring out, growing louder before halting abruptly. The room falls silent. Then, a splash of cymbals crashes before the brass section blasts. Thunderous bass and drums call the crowd to attention. Another brief pause and the audience’s roars fill the space, before the sequence repeats. The trombone and saxophones grow louder, while the drum patterns become increasingly intricate. Cheers and whoops grow deafening.

Finally, tension at a crescendo, the trombonist wanders up to the front of the stage, cloaked in the red glow of the stage lights. He grabs the mic, barking the name of the song — “SLOPE!” — and begins to bounce energetically. He leans down and grabs a bottle of Bucky, taking a healthy swig and then brandishing the bottle at the crowd. This, you might be surprised to learn, is jazz.

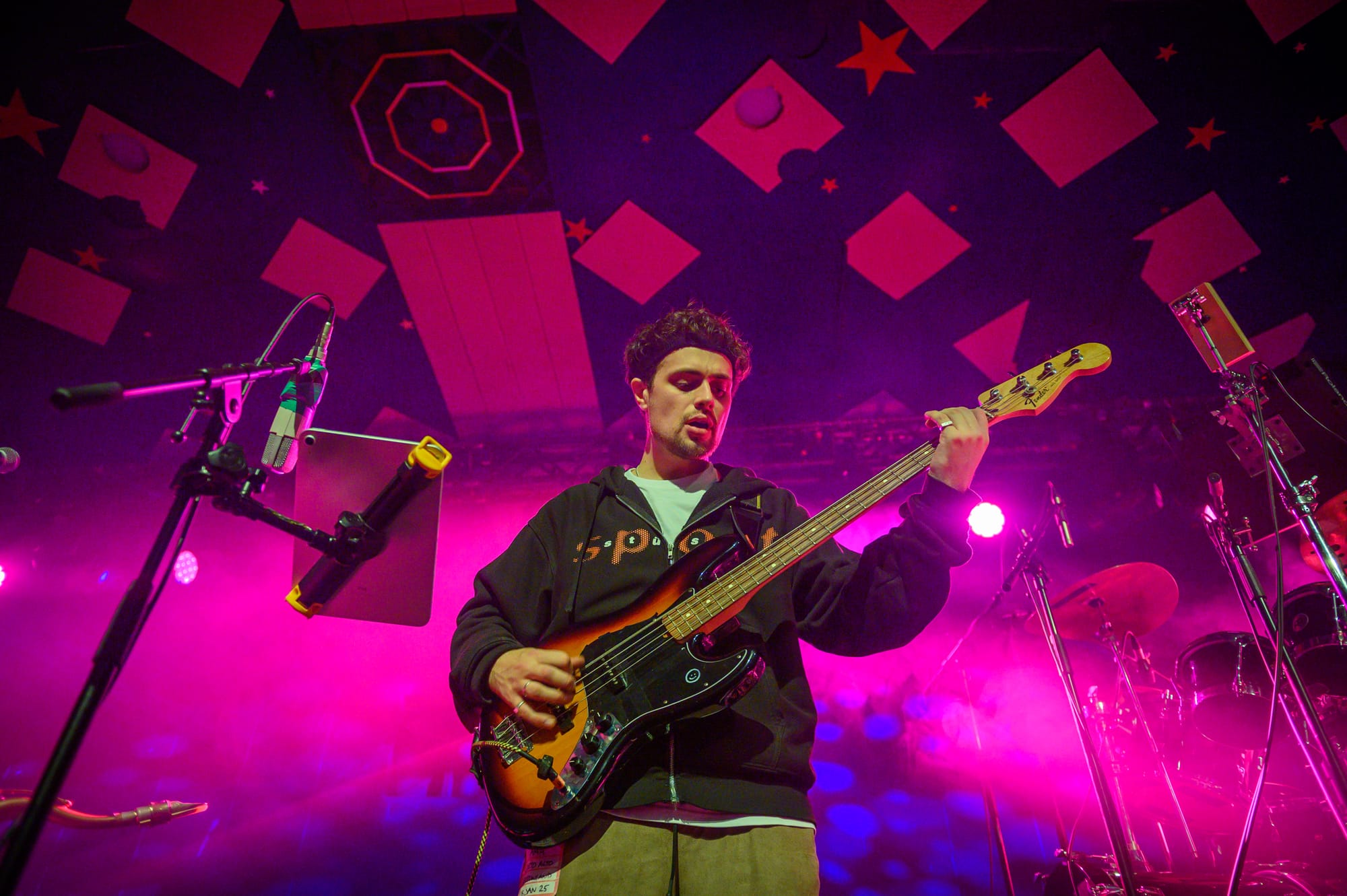

Tonight’s Celtic Connections show, ‘corto.alto + friends: MADE IN GLASGOW’, is a sell out. While London-based jazz group Ezra Collective sold out the same venue two months prior, this time it’s a local act, fronted by 28 year-old multi-instrumentalist Liam Shortall. This gig feels like something of a landmark for the burgeoning new wave jazz scene in the city. The crowd skews young. Some are fashionably dressed in leather studded flairs and backless tops, others more low key. There’s a distinct sense that at least half hail from the Southside, where the band are based — an instinct confirmed when Shortall later shouts out the area. “Anyone else live in Govanhill? Cheers! Wooh Vicky Road”. He takes another swig, and receives a loud response. Like at Glitch41, the improvisational night Shortall and his bandmate, saxophonist Mateusz Sobieski, put on at Rum Shack, a fug of weed fills the room, emanating from scarcely concealed vape pens.

After the first song ends, Shortall says thank you to the crowd for coming, appearing overwhelmed by the rapturous applause. He goes on to explain that he started the project with his pals six years ago in a flat he was living in on Sauchiehall Street. A few years later, Shortall's bandmate, jazz-folk pianist Fergus McCreadie, was shortlisted for the 2022 Mercury Prize — the same year he also won the Scottish Album of the Year Award and the Scottish Jazz Award for Best Album. Two years after McCreadie, Shortall was also Mercury nominated for his debut album, ‘Bad With Names’. Ever since, the spotlight of national attention has been turned towards Glasgow. But recent plaudits do a disservice to a diverse scene that’s been coming of age for a decade and a half, since the Royal Conservatoire started its jazz course back in 2009.

It’s a rainy Friday morning in Govanhill. We’ve had to reschedule our interview because of storm Éowyn, so we’re meeting a few weeks after the gig. Shortall greets me outside a café on Victoria Road, which Google Maps says is open. Our eyes say different: the shutters, unfortunately, are still down. “Govanhill cafés have their own time zones,” he says with a laugh as we move south to find an alternative location.

Fifteen minutes later, we’re sat at Sunny Acre, nursing twin oat flat whites, a cliché Shortall is visibly a little embarrassed about. We also both order the brown butter and sage eggs on toast. When Mary, the owner, asks if Shortall wants his with jamon, it triggers a moment of confusion; Shortall thought the eggs came with ‘jam on’, rather than Spanish ham. He should probably know better — his grandmother hails from the north of Spain. She married his grandfather, who had the name Shortall, hence the endlessly trendy styling of ‘corto.alto’: short, tall.

His phone buzzes. As he picks it up, he looks mildly frustrated. Young jazz students, he explains, regularly message to ask for sheet music, which he made available online during the pandemic. Someone subsequently recorded and then uploaded his music onto Spotify, without his permission, in their own name. Shortall, imperturbably laid back, isn’t that bothered, unlike his record label. The link is still floating around online, and so he still gets DMs pleading for access to the Google Drive. It’s not the only piracy concern he’s had. “Stop pirating my music you fucking donut,” @cortoalto wrote in response to a download link to his album on Reddit last year.

Shortall sees the Barrowlands gig as part of a slow burn over the past six years, in which the shows have slowly grown bigger and bigger, and the releases increasing in scope and scale too. “Walking out on stage to 2,000 people to watch instrumental music, you know — you've got no vocals, there's a lot of very intense improvisation. It was definitely a trip,” he says. “A lot of people think there's been a big jump, and there has. Last year the Mercury Prize definitely added a lot of weight behind the momentum of the project, but it's happened so incrementally and slowly.”

He’s “lucky,” Shortall tells me. He grew up surrounded by talent. “I've known Fergus [McCreadie] for over half my life, since I was 14. I've played with all of these guys for years, and we've really grown up together. We’ve had really hard times together, really great times together. And I think all that comes out with the music,” he muses.

McCreadie is six months younger than Shortall, but “he’s always been five years better than anyone else”. They got to know each other playing in the National Youth Jazz Orchestra of Scotland (NYJOS). “I'd never heard someone be that good at anything. He's definitely a big inspiration in my life.”

The NYJOS, like the jazz course at the Conservatoire, was founded by Scottish jazz legend Tommy Smith. “Since I was 16 I was on the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland jazz course, and since I was 13, I was a member of the Tommy Smith Youth Jazz Orchestra,” Shortall told the Barrowlands crowd in January. “This orchestra is a real privilege to play in. Out of everything I do it’s one of the most challenging things, and really rewarding musically — so I thought what better than to get the man who started this orchestra and the man who’s been a huge inspiration to a lot of other people.” Tommy Smith himself then swaggered on stage.

He wore sunglasses, a hoodie, a baseball cap and baggy trousers with his saxophone round his neck — the teacher dressed like his pupils for one night only. “I was looking at [my drummer] Graham, we both just started laughing at each other,” Shortall tells me, scooping eggs into his mouth. “We're playing a Jersey club beat at the Barrowlands, and Tommy's playing saxophone. I was like, How the fuck has this happened [...] It felt like a big circle moment, not to be cliché, but, you know, it was cool to do that.”

Like at the Barrowlands gig, Shortall repeatedly talks up the wider scene, rather than take the credit himself. “There's just so much happening in Glasgow, it's so hard to keep track of everything. It feels like every day, every week, there's new nights happening.” He references a Guardian article about the London jazz scene, where they chose seven artists and proclaimed “This is the jazz scene,” Shortall says. “It was a bit reductive and I think there's a risk of that happening in Glasgow as well. I'm definitely proud to be representing it where I can. But there are so many different scenes of people. I go to jam sessions and meet new people all the time,” he adds.

He reflexively contrasts the low-key, often DIY scene of Glasgow to the more established one in London. Glasgow, unsurprisingly, comes off better by Shortall’s metrics. “I think foremost, what's important to me is making sure people can access music no matter what their social or economic background is. I think that's what keeps the scene fresh and exciting,” he stresses. Glitch41 always offers subsidised tickets, as does Sobieski’s other night, Laylow.

Shortall also thinks the lack of established jazz infrastructure in Scotland — labels, promoters, venues, jazz-specific PR and radio — is an asset, not a hindrance. “In a weird way, it helped people not conform into a certain thing [...] It's very, very diverse sonically, there's no Glasgow sound. I think the sound of Glasgow is just like, all over the shop.”

Despite Shortall’s success, and slick trappings, cold hard cash is more elusive than clout. Take today’s outfit; from waist up he’s decked out in a Carhartt jacket, black hoodie and grey wool hat — a beanie has become his signature accessory. As has a professional relationship with Carhartt.

Nine months ago, Shortall again took to Reddit, this time to attempt to track down a package of clothes from Carhartt worth £2,000 that the brand had sent to him, before Evri, true to form, lost track of it. “I run an independant [sic] Jazz project, and I’m sure you can imagine that isn’t a very wealthy life,” he bemoaned. “Deals like this one (with bigger brands) are what help keep us going, and now this has all gone to shit sadly,” he wrote. If today’s garb is anything to go by, he managed to track down the shipment.

Plates cleared, we head out onto Pollokshaws Road. An English guy comes over to bump his fist. “Big fan” he says, “Saw you at We Out Here in Bristol.” Shortall isn’t totally accustomed to being recognised, and is still caught out by it at moments like this, or when on a night out with pals.

Over email from Germany where he’s currently touring, Tommy Smith explains the long and often thankless task of setting up the Conservatoire and National Jazz Orchestra. When he returned to Scotland in 1993 after living abroad and touring the world, he “witnessed a lack of jazz infrastructure, leadership, and opportunity in Scotland compared to many countries where I had taught and performed”. He set out on the task of creating a full time jazz course. By 2001 he was writing to the First Minister Jack McConnell and speaking to universities where he taught part time. “Then, in early 2009, like a dream, I received a telephone call […] ‘We’d like you to head up a full-time jazz course at the RSAMD’. The principal of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (now the RCS), John Wallace drove to his house. “The rest is history,” says Smith.

Just before lockdown, Smith visited all the venues across the city where RCS students were performing for the first time. “[I] was humbled by their determination to make a scene. Everything and everyone inspires everything and everyone.”

At the Glad Café, I meet with musician Emilie Boyd, an old university pal who runs Jazz at the Glad. “I would say we landed at a moment where the contemporary jazz thing is quite popular, while still being quite fresh,” she says. “We get a lot of people coming who are like, ‘Oh, I just thought I'd try this. I would never go to jazz’.” Despite the crowd I witnessed at the Barrowlands, Boyd says jazz has been a “hard sell” in Glasgow because the word is “boring, old fashioned”. It’s the under 40s however, who are breathing new life into the space.“There's this young, fresh scene who really want to do creative stuff, and those gigs sell really well amongst the young people, which is cool,” she adds.

She makes a point to acknowledge that there's “definitely been a big problem with racial diversity in the [Glasgow] jazz scene” because the city is “a lot whiter than, say, London or Manchester”. “I think it's just something to always be aware of and always be conscious — that we're playing music of and profiting off of music that's essentially of black origin, and to try and be as inclusive as possible,” she adds.

When Shortall studied at the RCS, it was de rigueur that artists graduated and moved away to seek their musical fortunes. Now, the situation has upended.“Every year there's like 10 new really, really good jazz musicians, maybe two or three of them move away. The majority of them stay,” he explains. “I think you really started to notice that kind of the accumulation of graduates coming in and starting new stuff and staying in Glasgow. I think it just took a few years of people kind of trying something here [...] to encourage other people to do that. Now it's snowballed into a bigger scene,” he adds.

One of the lines often trotted out about Shortall, presumably by his record label, is that he’s “a traditional jazz head raised in the age of the internet”. Through repetition the phrase has lost some of its genuineness, but there is a large degree of truth to it. After corto.alto and Glitch41 gigs, slick portrait videos and crisp stills often emerge, easily shareable and digestible for social media. Both the band and its loyal fanbase seem to push against the stereotypes of jazz’s stuffier scene, all the while respecting the craft, musicianship and classical training. Drawing from a wide diversity of styles and genres, Shortall is determined, more than anything, to make jazz accessible, especially with the Glitch improv gigs.

“I think the goal should be everyone with what they've got makes music together for the audience,” he states. “They shouldn't be like, ‘Who knows this tune?’”

A lot of gigs, he claims, are “posturing”. For who? “Other jazz musicians to show that they know more than them, which is a load of shit, man. You're there for the people in the audience who maybe don't work in music, and maybe work a job they don't like, they're trying to switch off. They're not trying to watch you be competitive with each other,” he says.

At the end of the Barrowlands gig, Shortall shouts out all the support acts, the sound desk and all the musicians on stage, as well as their various musical projects, most of which overlap and interconnect. “When you get into this sort of music, you don’t expect this to happen,” Shortall tells the crowd, launching into the encore. It won’t be his last.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.