Lately I seem to be getting The Fear a little more often than usual. It could be the drinking (too much) or the sunlight (too little) or watching the streets of Glasgow slowly transforming into tarmac-black rivers that come wet and gurgling out of the gutters. These are bad times really. The neighbour's cat has stopped leaving the house for fear of being blown into oncoming traffic, and I feel the same, only venturing out for the thirty second jog to the pub. I go to the pub to escape The Fear. When I return home, The Fear is sitting smoking on my doorstep, ashing into the hydrangeas.

The Fear only seems to affect me in Glasgow. There’s no other city so thoroughly afflicted by shame and social anxiety (or perhaps nation, at least according to Carol Craig’s 2004 work ‘The Scots' Crisis of Confidence’).

You may think this is a sweeping statement, but I’ve worked in self-deprecating Birmingham, self-pitying Liverpool and self-fellating Manchester and in none of these places are people afraid to be seen purchasing loo roll in case someone asks them if they’re away home for a shite now, aye? But in Glasgow this is just another day at the Big Tesco. We give each other The Fear because we’re consumed by it ourselves.

And the fact is that, however much I’d like to be, I’m not the first to say it. The concept of ‘Scottish Cringe’ — an alleged sense of cultural inferiority in regards to England, leading to feelings of resentment and embarrassment, (and, according to ex-First Minister Jack McConnell, opposition towards free-market capitalism) — has been well documented and needn’t be elaborated upon here. But among the younger generations of Glaswegians (namely the 20-somethings such as myself), Scottish Cringe has evolved, been replaced even, by a Glasgow-specific strain of the affliction. This is Riddy Culture: the “fear of being judged for doing anything outlandish, expressive, unorthodox or outwith social norms” (thank you, Urban Dictionary).

There is no clear record of how and when the term ‘Riddy Culture’ was born, but its component parts are traceable enough. The term ‘riddy’ is an old one. The Dictionary of the Scots Language, under the section for ‘reid’ and all words red-adjacent, defines a ‘riddy’ as “a blushing face from embarrassment; the cause of such embarrassment” — a definition taken almost verbatim from Michael Munro’s 1985 Scots dictionary, 'The Patter'. When The Herald featured ‘riddy’ as their Scots Word of the Week last May, they gave an example of it in situ from The Glasgow Evening Times: “This guy ‘gees us aww a riddy’ by appearing in Google maps with his taps aff”.

A riddy was originally something that you got, or else it was something that happened to you. Tripped up crossing the road in front of an entire bus full of teenagers and one of them cracks the window open and calls you a cunt? That’s a riddy. On a date while that happened? Your date probably got a riddy as a result.

Then there was a turning point sometime while I was in secondary school (I’m not telling you exactly when that was lest this piece lose some of its authority, but let's just say after 2010), when all of a sudden a riddy became not just something that happened to you, but something you could be. More importantly perhaps, it became something to make sure at all costs that you weren’t.

This proved to be a near impossible task. The list of things that could warrant you getting called a riddy was as extensive as it was absurd. It included, but was in no way limited to: playing an instrument, reading a book, buying a thing from a shop, listening to any music other than Capital radio, listening to Capital radio, and sincerely attempting virtually any creative, or in any way, ambitious pursuit. The solution, naturally, was to avoid doing anything at all that could cause you to stand out from the status quo. A new riddy era had officially commenced — now it just needed a name.

It was to find one in the late Noughties. The oldest documented use of the term ‘riddy culture' I've managed to find, following thorough searches of The Internet, is a tweet from 27 November 2018, from a Twitter user called Jake. It goes as follows: “End riddy culture. Imagine finding a hobby fuck them right?” [sic].

For the next couple of years there was the odd mention of the phenomenon on digital platforms. But from 2021 the phrase boomed in popularity. A tweet from that year saying that “Glasgow riddy culture is the worst thing about Glasgow” received 22,000 likes. More recently, a Reddit post from last July asking Glaswegians for their experiences of riddy culture garnered 343 comments, most of them providing examples, and a few of them accusing the asker of being a riddy.

Multiple responses to the post describe being heckled on the streets of Glasgow for carrying a guitar. One man recalls getting the piss taken out of him for bringing ‘Tory rolls’ (see: brioche buns) to a barbecue. “[L]eft my flat in white jeans once,” wrote Reddit user slackscassidy, “and without a seconds hesitation a 12-year-old kid yelled across the street ‘late for fuckin karate?’”

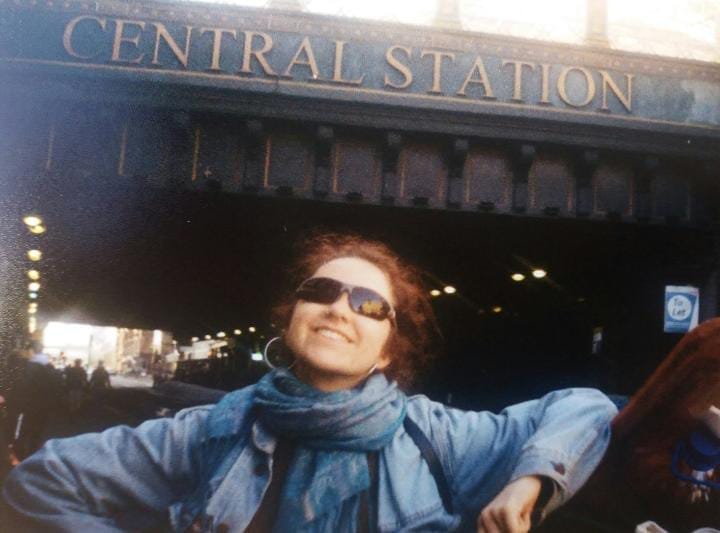

However, in order to properly confirm that Glasgow is a city unusually afflicted with The Fear, I had to put online discourse aside and take to the city centre streets. Unfortunately, asking randoms on the street questions for an article is decidedly riddy behaviour, and responding to them is even worse, so eventually I desert the streets for the pub, where I have considerably more success. Here I meet with an old friend and self-confessed riddy by the name of Roisin McCann — we grew up in Glasgow together in the 2000s, both of us prime targets for riddy culture’s clammy grip. Roisin has somewhat reclaimed the term, using it as a positive identifier.

“I guess a riddy refuses to comply with the strict code of self awareness that being Glasgwegian involves,” she explains. “Which means showing no genuine emotion, and hiding what you care about or would like to explore as a skill or hobby.”

In Roisin’s experience, while being successful at something is naturally lauded in the city, attempting or practising that same activity is not. “Exhibiting the vulnerability of being an amateur in Glasgow is quite embarrassing,” she says. “If you saw someone trying to rollerblade on the Clyde you’d be like… we’re not on Hollywood Boulevard.”

So what behaviours spring to mind when imagining the archetypal riddy? Roisin immediately cites reading in public. This bothers me, as I had been reading in public the night before. “I read in public too,” she replies hesitantly, “just not in Glasgow”.

More niche examples include people involved in the Glasgow Art School scene, and anyone skating on a longboard. Certain food and drink choices are riddy too. “If you had sat down with a WKD right now,” she tells me, “that would be such riddy behaviour.” Luckily I have ordered a pint of Tennents, precisely in order to avoid such an outcome.

How is Roisin overcoming the effects of riddy culture? “I’m really, really trying to just do the things I want to do,” she explains. This includes getting back into skateboarding and not being ashamed of listening to The 1975 (I do not support this). She also tells me that she recently joined a football team, despite being terrible at football. “I’m really bad,” she says, “but I’m refusing to let that get in the way. And there’s no riddy police there, everyone’s really supportive.”

In light of this, Roisin sees being a riddy as a thing to be celebrated. “Riddys are aspirational and open to trying new things. But I feel like a lot of people have to leave Glasgow to explore the skill they actually want to work on.”

Tom Dixon, 26, is one such young Glaswegian, departing the city last September in favour of a new life in London. “Everyone has riddy behaviours,” he tells me when I ask him if he’s a riddy. “Mine at the moment is having polo mints.” Does he offer them to people in London? “Yeah, I have been.” Would he offer them to people in Glasgow? “I think I might be a bit embarrassed,” he replies.

Growing up in Glasgow, Tom was well acquainted with riddy culture: he recalls being 17, on a bus home from town, when he accidentally pressed the stop button a little too early in his journey, prompting a middle-aged man to turn to him and ask him if he was “a fucking clown”. “I felt very ashamed of myself,” he laughs. “I think it was one stop before we were meant to get off.” Luckily, he’s experienced no such thing in the English capital, and he even assures me that reading in public is considered respectable on the tube.

In ‘The Scot’s Crisis of Confidence,’ Carol Craig writes that the crisis “is not a crisis of identity for Scotland — Scottishness is strong — but rather what it means for the individual […] Scottish culture constrains and limits individuality”. This may be a generalisation — and similarly it would be ridiculous to suggest that all Glaswegians are affected by riddy culture — but I think the general sentiment rings true for Glasgow too: that our identity is so strong as to be stifling.

It can often seem that Glaswegianness is less of an innate trait or a learned cultural behaviour, and more of a strict set of rules to be adhered to. Is this an after-effect of Glasgow’s joint influences of Presbyterianism and Catholic guilt? Is it a localised version of a global phenomenon — that of social media encouraging young people to package and post their identities to an audience? Is it just plain old Scottish-cringe on the comeback? Is it even all that bad?

“I think in Glasgow people are so much more open to making fun of you, but if you’re open to being made fun of then the conversation continues,” says Tom. “Whereas in London, no one's gonna make fun of you, but the conversation just won’t happen at all.” Tom doesn’t even necessarily believe that the fear of being a riddy — or being ridiculed — has ever actually kept him down. “I think in Glasgow there’s an air of not wanting to stand out too much,” he says, “but when you own it, everyone leaves you alone.”

What's the worst riddy you ever hit and why? Do you reject the entire concept of riddy? Comment below.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.