When Samantha Cooper first opened her shop on Glasgow’s ancient High Street, an old man stood in the doorway and shook his walking stick at her.

“It’ll never work,” he said, disapprovingly.

Nearly 30 years on, Samantha is still making it work – just about. She and her store, 23 Enigma, claim to be the city’s (and Scotland’s) oldest retail trader in the occult, although Samantha prefers the term ‘esoteric’. But she’s on the brink. In September, amid displays of crystals and books on paganism, a handwritten sign was lodged in 23 Engima’s window.

“My Glasgow Council landlord[‘s] shop is rotting and they refuse to relocate me,” it reads. “Council taxpayers are funding High Street Managed Decline. This is unjust, unsustainable and unethical”.

Ask Samantha about this sign, and it quickly becomes apparent this battle is not new. Since 2013, there have been campaigns, extensive press coverage and even an independent documentary, produced by High Street’s commercial tenants. A fresh-faced Samantha, with long, glossy brown hair, anchors the film.

Today, her hair is a shock of grey. Most of the tenants who appeared in the documentary have left High Street – ‘To Let’ signs on sandstone tenements mark their absence. High Street is the oldest thoroughfare in the city, snaking up to Glasgow Cathedral, which welcomes hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. On their way, many hurry past the vacant retail units of High Street. Like the nearby Necropolis, this stretch of road is a graveyard.

For commercial tenants this geography should be a gift. But over 40% of shopfronts currently lie empty and crumbling. Traders say their efforts to fix issues and secure the future of High Street have seen them pushed to the edge of their financial and mental limits by a confusing labyrinth of institutional bureaucracy.

‘City Property are not interested’

Low footfall isn’t a cause, but a symptom of High Street’s issues. 23 Enigma, despite the odd handwritten hate letter, has a steady stream of patrons, from 80-year-old pensioners buying tomes on Celtic literature to students who’ve developed a taste for tarot from TikTok. In 2009, trading was going so well for Samantha and her business partner, Andrew Moloney, that they expanded into a second High Street premises: Ladywell, named after the nearby holy water source.

Ladywell, the pair discovered, had chronic dry rot. It was historic, Samantha says, something she should have been informed of before taking up the lease. She reported the problem to the relevant authorities. Unfortunately, at the very moment she did this, the relevant authorities suddenly changed.

In 2008, commercial traders on High Street would have been dealing with the city council as their landlord. In October 2009, a new player entered the fray: City Property Glasgow LLP, the arms-length organisation (ALEO) created by the Labour-led Glasgow City Council to manage, develop and – when required – dispose of Glasgow City Council’s property and land assets. A year later, City Property ‘bought’ all of the city council’s nearly 1,400 strong property portfolio and mortgaged them to Barclays bank, in exchange for £120m.

These funds were used to bankroll a series of controversial early retirement payouts to council officials. Since then, City Property has sprouted various commercial heads in order to manage other financial manoeuvres, including remortgaging Glasgow’s formerly-council-owned buildings to finance the city’s equal pay debt. Currently, the City Property Investments (CPGI) arm is responsible for High Street, but for the sake of brevity, we’ll refer to them as City Property from here on out.

With City Property on the scene, Samantha and Andrew found themselves in a six-year fight to get Ladywell’s rot problem fixed. But communication was bewildering. Responsibility for the repairs were being ping-ponged between City Property; City Property’s then-agent, Ryden; and YourPlace, a subsidiary of Wheatley Homes, Scotland’s largest property management group (and housing association).

Since 2003, residential tenants who live above High Street’s shops, most of whom own their flats, have had their tenements managed by YourPlace. Just to make matters more confusing, since a 2021 merger, YourPlace now operates under the name Lowther in this area. Both of these companies are still under the Wheatley Group umbrella.

Letters to Samantha and Andrew regarding Ladywell reflected the mish-mash of multiple institutional cooks, none of whom seemed to know who was ultimately in charge of the broth. Crucially, only minor repairs were completed.

This seems to be a key theme for High Street. At number 269 I meet Naveed, who only gives his first name. Over seven years, Naveed has repeatedly reported ceiling leaks in his international grocery store. Fridges have broken as a result of the problem and he’s lost stock.

Naveed says he’s emailed City Property multiple times but received no response. Company officials occasionally visited the shop but his issue went unresolved so Naveed eventually told them to get out.

“I said, ‘No, if you are coming just for looking, go away’,” he recounts. Naveed ended up replacing the fridge himself, at a cost of £3,800. Meanwhile, rent was going up. After High Street was closed for five months in 2023, for urgent sewer repairs, Naveed took out a loan of nearly £18,000 to keep the business afloat. He currently works 14-hour days to make back the cash. While the leak seems to have stopped, he’s got no idea who might have fixed it – and there’s been no contact with local councillors either.

“If you speak with the councillor, they have to speak with City Property, and City Property are not moving,” he says. “City Property are not interested in this part of High Street.” Naveed believes the organisation wants to develop High Street and is deliberately neglecting commercial tenants to push them towards leaving.

This is a common conspiracy theory among High Street traders. They cannot understand why else an organisation that claims to be furthering Glasgow’s economic future would allow such a prime urban spot to wither and die. “All City Property needs to do is repair the shops and rent them to sustainable businesses,” Samantha asserts. “The only explanation of why they don't is they have adopted a policy of managed decline.”

The reality seems more prosaic, a mix of buck-passing between institutions, poor communication, and clashing visions of what ‘value’ entails. We put this to City Property, who replied with a statement saying that their “commitment” to High Street is demonstrated via “offering refurbished units to the market for start-up businesses, social enterprises, creative organisations, community groups and other complimentary SMEs etc”.

The primary problems plaguing High Street are simple: damp and rot. But the layers of bureaucratic sediment commercial tenants have to sift through to try and get any movement on the issue are mind-boggling.

Restricted remits

City Property is very willing to collect – and raise – rents. However, the company has strict limits on its other responsibilities. Large infrastructure repairs that go further than the four walls of the shop covered by the commercial lease become ‘common repairs’, and thus the responsibility of the residential building factor. On High Street, this means most of these rot repairs were passed on to YourPlace.

If common repairs are projected to cost more than £2,000, the property management company has to get the majority of residents to sign off on them and stump up the cash. What’s more, if repairs affect two different buildings (for example, impacting shared back courts), they need unanimous agreement from residents of both blocks.

In High Street’s multi-storey tenements, commercial residents could also be stuck paying individual repair costs passed onto them by City Property and share the burden of common repair costs required by the housing association. That’s if residential tenants are willing to agree to repair costs in the first place.

In a letter sent to Samantha Cooper and her business partner in May 2013, YourPlace highlighted what would happen if High Street residents refused repairs requested by commercial tenants. “Where we can’t proceed with major repairs because the owners will not, or cannot, agree to them, we sometimes have to accept that the effective decision is that the repair will not proceed,” it read.

Judging from conversations with multiple sources, including within the property management company and council, this seems to be a key piece of the puzzle in understanding why the necessary repairs aren’t happening. Some residents within High Street’s tenements, understandably, don’t want to pay. So repairs don’t get done.

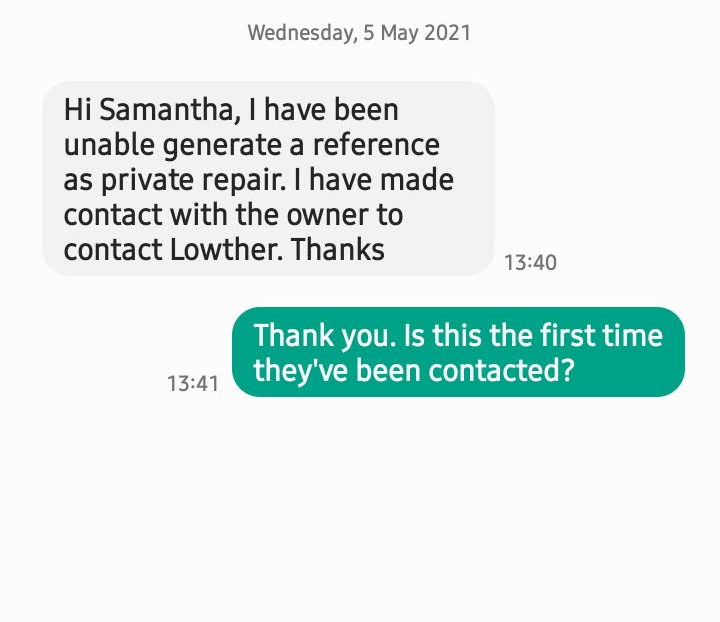

But this information hasn’t been conveyed to High Street’s traders. Samantha keeps an extensive physical and digital archive of communications relating to her case. I ask her if she recognises the name Lowther. She doesn’t, but she later digs up a single text message from 2021, where an unnamed City Property official says they have made “contact with the owner to contact Lowther”, in reference to a report Samantha lodged about a flood in the vacant bubble tea shop next door. Samantha then asks whether Lowther has been contacted before, but she receives no reply.

In lieu of information, Samantha, like Naveed, kept petitioning City Property to sort out the situation. So did others, like Gordon Jennens, at Glasgow Appliances, and Daniel Taylor, who ran celebrated cafe McCune Smith. Both have since packed up and departed High Street; Jennens after telling a radio show he was suffering from PTSD linked to his attempts to sort out persistent problems in his store caused by damp and rot.

Taylor, who revised initial plans to open a design shop once he realised the scale of renovation needed on his rented High Street unit, finally gave up his internationally renowned cafe in 2019 after a “35% rent hike”, Samantha says. The Bell reached out to both men for comment, but they didn’t reply.

City Property does occasionally communicate: with the press. As traders ramped up their protests, the organisation fought back, particularly against Samantha, who had become the most vocal commercial tenant on the street. Any repairs needed at Ladywell were “due to a lack of maintenance on her part”, a City Property spokesperson told Herald reporter David Leask in 2013. At this point, Samantha had only held the lease for four years.

If you're reading this and you haven't yet joined our free mailing list, click here to get Glasgow's new quality newspaper in your inbox every week.

More recently, in Glasgow Live, the company blamed ongoing rot and damp in 23 Enigma on a “build up of condensation behind tall storage cases”. They also cited an outstanding management fee payment Samantha owes, part of a rent strike she went on during her campaign to save Ladywell. It didn’t work. In 2017, Samantha and Andrew were served notice to leave the shop.

An accompanying letter from City Property informed them that: “Given the unreasonable stance that you have continued to adopt, regrettably I am now of the view that the landlord/tenant relationship is not sustainable.” Since then, communication has almost completely broken down.

Today, Samantha is intensely isolated. Multiple sources, including Samantha herself, tell me that she has essentially been “blacklisted” by City Property for being “difficult” and obsessive. The Bell put this allegation to City Property, who said they “cannot provide comment on individual tenants/tenancies”. Others were happy to: Samantha has become fixated, says one member of the city council, who confesses they try not to deal with her. But, when faced with such circumstances, wouldn’t anyone?

“Everybody is terrified of City Property,” Samantha says tearfully from her counter in 23 Enigma, where she has retreated. Her words are soundtracked by the hum of an air purifier attempting to dispel the smell of damp for browsing customers.

“They have the power of life or death over your business. We're just basically waiting for another eviction. It's psychological torture”. Samantha’s personal relationships and mental health have collapsed with the stress, she says, while a chronic health condition has flared up.

What now?

Elected officials have also reached the end of their tether. “I’m at a loss,” says Christy Mearns, Green Party councillor for the ward. Technically, Mearns is responsible for one half of High Street; the other half falls into Dennistoun and the jurisdiction of her Green colleague Anthony Carroll. Mearns admits that she and Carroll have not “sat down extensively” to try and jointly tackle the High Street problem, although they have discussed it informally at length.

But Mearns, who is energetic and clearly passionate about High Street, says she’s been working for seven years to try and get movement on the issue – she even secured a seat on the City Property board to try and advance High Street’s regeneration. At every possible avenue, she’s been met with a brick wall. During her 2017 election campaign, she pledged to “investigate” City Property – something she regrets. “I was new to being a councillor, I didn't really understand how it all worked,” she says. “I made promises, which I maybe shouldn't have done in hindsight, about what I would do if elected.”

You can’t ‘investigate’ City Property, she says. There’s no route for that as a councillor. And besides, they are, technically, “performing their functions properly.” How? “Because their functions are so limited,” Mearns explains, with frustration. “They don't need to do all the other bits.”

She outlines again the block on common repairs that neither City Property nor Lowther are willing, or even allowed, to solve. (In a statement, Lowther told The Bell that: “We do not own the building. As factors, we are responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of the communal areas, such as the stairways, hallways, back courts and lifts. Repairs within the commercial units are a matter for the leaseholder and the owner of the shop units.”).

Mearns raises doubts about whether some repairs have even been put to residential tenants for their approval. She keeps asking for the data, she says, for a breakdown of the exact work needed, with associated costs. “I can't tell you how many hundreds of times I said, ‘can you please send me details?’,” she tells me. If it exists, she’s not been made privy to it. After a year on maternity leave, she thought she would come back to find something on her desk. But no. Neither City Property nor Lowther seems to want to shed light on this. “I’m a broken record,” says the councillor.

During deliberations over City Property’s latest business plan, Mearns says she tried to make the case for lowering rents for commercial tenants on High Street, with additional support for long-term occupants and that maybe – just maybe – some of Glasgow’s capital investment fund could be put towards the cost of repairs, even if it’s not technically their responsibility.

But the institutional mindset of City Property does not lend itself to creative thinking. “When I raise these things, the main argument [against them] is that the funder wouldn't allow it,” she says. Up until 2019, this was Barclays. Now it’s a US insurance company.

City Property says they offer commercial tenants “various solutions on a case-by-case basis, this being balanced against CPGI’s own financial covenants”. Mearns has a different take.

“I don't think the strategy that they're insisting on is working,” she says, carefully. “For me, it's not about being right, it's about doing something that actually works.”

Back on High Street, deterioration continues. But one new tenant is chipper. Caffe Mulberry opened in December 2023, next to the abandoned shell of what was once Glasgow Appliances. The interior is warm and cosy, with cookies and sweet treats stacked enticingly high. The owner, who asked not to be named, describes his relationship with City Property as “very tough”. His lease began in 2022 but flood damage to the unit delayed opening. Yet there was no rent rebate from City Property, despite Caffe Mulberry being selected by the company to take up occupancy over several other applicants. “All my own money has been put into [the cafe] to make it happen”, he says. “I've had nothing back”.

Still, he’s optimistic about High Street’s prospects – he sees the potential other tenants do. I ask about footfall which I’ve heard is down. Mulberry’s owner cheerfully claims it’s fine, although he admits they will soon test late-night opening hours, offering the likes of pizza and pasta to lure in students from nearby accommodation blocks.

Two wander in as we speak; primary education students from the University of Strathclyde, who report it is their first time in the cafe. Usually they go straight to the Student Union; High Street isn’t really a draw for them. Iced coffees in hand, they pledge to come back.

That might take a while. A few days later, Caffe Mulberry is shuttered, the doors locked. Another flood, Samantha says. Scrawled on the window in white pen is a familiar refrain for High Street: “Closed for renovation”.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.