Paul Sweeney MSP is showing me a picture book. The slim volume in question — Old Springburn — is actually his second copy. The battered original, he keeps at home. It’s an heirloom, you see, his “ground zero” text, as the 36-year-old describes it.

As a little boy growing up in Springburn, Sweeney would sit on his grandma’s knee, poring over the book’s black-and-white photographs of a place that was all but eradicated by then. Springburn is the archetype of a very specific Glasgow story: a grand, industrial neighborhood subject to massive regeneration in the 1970s and 1980s. Eighty-five percent of its buildings were destroyed and 60% of the local residents shunted out. Then the urban renewal project stalled.

By the time Sweeney — the son of a bank clerk and a shipyard worker — was born, Springburn was a byword for bungled development. One fragment of the area’s former glory remained: the Springburn Public Halls, although it was abandoned by the time Sweeney was toddling the streets.

“I used to stare at this photograph,” Sweeney tells me, fingers wistfully caressing the 2D outline of the Halls. He’d hear stories from older generations about dance recitals and Christmas parties held there. While other kids were daydreaming about becoming footballers, Sweeney says he would fantasise about the Halls being restored. “I even used to build it out of Lego,” he chuckles.

He had so many questions. “Why would you tear down something so lovely?”, he would muse. “Why can’t we just fix it up?”

This likely won’t come as a surprise to most of Glasgow. Sweeney has carved out quite a niche as a champion of the city’s built heritage. Almost every week, a local newspaper carries a picture of the Labour politician standing in front of a different crumbling facade, arms folded, pale blue eyes flinty.

This isn’t a branding gimmick. Sweeney — a polymath with a background in both political economics and engineering — is genuinely obsessed with Glasgow’s architectural history. All of its history, actually.

During our 90-minute conversation, I frequently find we’re on an enthusiastic diversion. I learn about the Scotsman who built Britain’s first motor car (subsequently receiving the first joyriding fine after driving it down Buchanan Street); that the city had the second-biggest municipal housing system in the world in the 20th century; that Loyalists were bombing Calton pubs during the Troubles, and that Billy Connolly’s autobiography contains a very funny story about Anderston grannies and Afghan melons that Sweeney thinks is a striking illustration of urban coherence lost in the postwar reconstruction of the city.

“Sorry,” he says, shamefacedly. “I rambled on”.

Paul Sweeney does talk — a lot — but it’s not rambling per se; it’s all relevant information, because he’s trying to demonstrate how everything is connected, see? A visual communicator, he’ll often spring up from his chair and point to one of the brightly coloured maps or framed drawings of ships that line the walls of his spacious Merchant City office.

We got to Billy Connolly from built heritage because he was trying to explain why Glasgow “gets a raw deal”.

“There’s no moustache-twirling dastardly villain,” he says, then checks himself, adding “well, there is a broader neoliberal agenda which has dismantl[ed] Glasgow’s once proud municipal socialism”. But the modernist planning of the late 20th century is also to blame, Sweeney claims, citing The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs, one of an extensive bibliography we’ll rack up by the time I switch off my recording device.

Jacobs referred to the massive financial investment made in modernist urban planning projects, like Springburn’s demolition, as “cataclysmic money”, Sweeney recounts. “This idea of ‘we’ve got a social problem, let’s machine gun it with money to fix it’. But then you’re missing the fine grain of what actually makes a community work”.

The eventual flattening of his beloved Springburn Halls in 2012 was one of two “radicalising moments” Sweeney highlights during our time together. He was already involved with politics by then, having joined the Labour Party in 2008. In 2009, he received a phone call from Sarah Brown, wife of prime minister Gordon. Would Paul assist with local campaigning efforts in the North East ward?

Sweeney did, and his star rose further until he eventually became Labour’s candidate for a Westminster seat in 2017. Then 28, his victory in Glasgow North East — which he attributes to a surge of support for former UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn — was such a surprise, he hadn’t even bothered writing a speech.

Two years later, he was supplanted at the general election by the SNP’s Anne McLaughlin in a loss Sweeney said felt like a “public execution”. Labour were loath to lose him for good, though. By June 2021, he was back as a frontline politician, this time in Holyrood, representing the Glasgow region.

Even if Sweeney doesn’t say it, I can’t help but think his time out in the political wilderness — which saw him forced to rely on Universal Credit as the job market slowed during the Covid-19 pandemic — laid the groundwork for what he frames as his second major ‘radicalising’ moment, in 2023. It also took place in Springburn, this time in the Marie Curie hospice, near where he grew up — Sweeney’s high school used to do fundraisers for the place. In 2023, the hospice was once again raising money, this time for a new building; Sweeney went along to help.

He was popping in and out of rooms, saying hello to the residents. In one cubicle was a woman in her early 40s; let’s call her Fiona. Fiona was from Bridgeton; she had a past that healthcare clinicians would describe as ‘chaotic’: sex work and drug use. By the time Sweeney met her, though, she was settled and felt her life was back on track.

Or had been. A few years earlier, Fiona was struck down with a nasty case of what she suspected was tonsillitis. She went in to see her GP and was sent away with painkillers. But the complaint didn’t go away. Fiona kept going back, asking for further investigation, but she was dismissed. Occasionally she got a prescription for antibiotics.

“She didn’t feel like she’d been taken seriously,” Sweeney tells me.

By the time Fiona received a throat cancer diagnosis, it was far too late. In the hospice, she grunted her story to Sweeney, constrained by the tracheotomy that had failed to slow the cancer’s spread.

“She died the day after I visited,” Sweeney remembers.

The entire experience was a shock, accompanied by a creeping realisation that Fiona’s death was the result of “social injustice”. “Maybe if I lived in Milngavie, I wouldn’t be dying,” Fiona had said to him.

Quite a delayed lightning bolt for a Labour MP who’s seen as pretty attuned to the social landscape, I prod.

“You can look at statistics and take an abstract view of it,” Sweeney says, honestly. “You know, people might die of a drug overdose because they’re more likely to take drugs in a poor community. But I realised there was maybe a subconscious bias where a woman from a working-class background might find it harder to access healthcare that therefore resulted in her premature death”.

Sweeney’s come-to-the-light moment was one of great “grief”, he says. “The enormity of the realisation and feeling of loss and anger at [Fiona] not being able to feel the reward of having rebuilt her life…” He trails off.

Where did encountering Fiona leave him, I ask. How would he describe his politics now?

“I don’t have a neat ideology the way I [once] did,” Sweeney muses. Blanket solutions like nationalisation, that he used to support wholesale, made it easier to privatise much of Scotland’s assets, he believes. His present political approach is one formed from observing “social injustice in Glasgow and trying to address it in a practical way. How do you embed community agency and ownership in a way which is sticky and can’t just be undone in a political cycle?” he asks, rhetorically. He’s very drawn to the co-operative movement.

He goes on: “a lot of my political understandings have been coloured by a sense of what a wasted opportunity Glasgow’s had”. But Sweeney rejects the fatalism that hangs over the city. “A lot of Glaswegians have developed a lack of expectation of things improving,” he notes, frankly. “That’s coloured their alienation from politics”. A large part of his passion for built heritage comes from the psychological impact he believes its restoration can have.

“My Springburn Winter Gardens project,” Sweeney references, before correcting the slip of the tongue. “Well, it’s not mine as such, but I’ve been involved with it for 10 years”. The glasshouses, like many across Glasgow, are derelict, and Sweeney is trying desperately to renovate them. Lots of local residents tell him: “that’s never going to happen Paul, you’re wasting your time”. He stubbornly refuses to give in. “We’ve kept it standing with the hope that it will be restored as a defiant symbol of rebirth for the area”. I can’t tell if he’s completely tuned into the unconscious needs of his constituents or just channelling his own.

Post-Fiona, parity has swum further into focus. “It’s one thing to have equality of access; another thing to have equity,” he stresses. Public services have to be improved, obviously, but it’s taking enormous energy to maintain what already exists, he says.

“What about the welfare cuts planned by UK Labour?” I ask.

Sweeney sighs and tells me he was discussing this on Easterhouse doorsteps during the recent North East by-election campaign. (Labour lost to the SNP.) “I think a blunt approach to cutting welfare would be socially unjust,” he says.

“But you have to combine that with, ‘well, why is there a system disincentivising people from access[ing] work?’. If I’m understanding proposals correctly, how do we deal with someone’s individual circumstances and give them support to access employment where they otherwise wouldn’t be able to?”

I think he’s being overly generous about plans to slash benefits, but Sweeney quickly follows up by turning his attention to pay. “Most people in the social security system are in work,” he continues. “[Their need for welfare support] is the product of low wages. How do we gear up the economy by increasing average wages and therefore the tax base?”

He pulls the conversation back to his priority: Glasgow. “And then there’s issues around transport and access”. His mother, still working in a Motherwell bank branch, “can’t afford to get to work” via public transport.

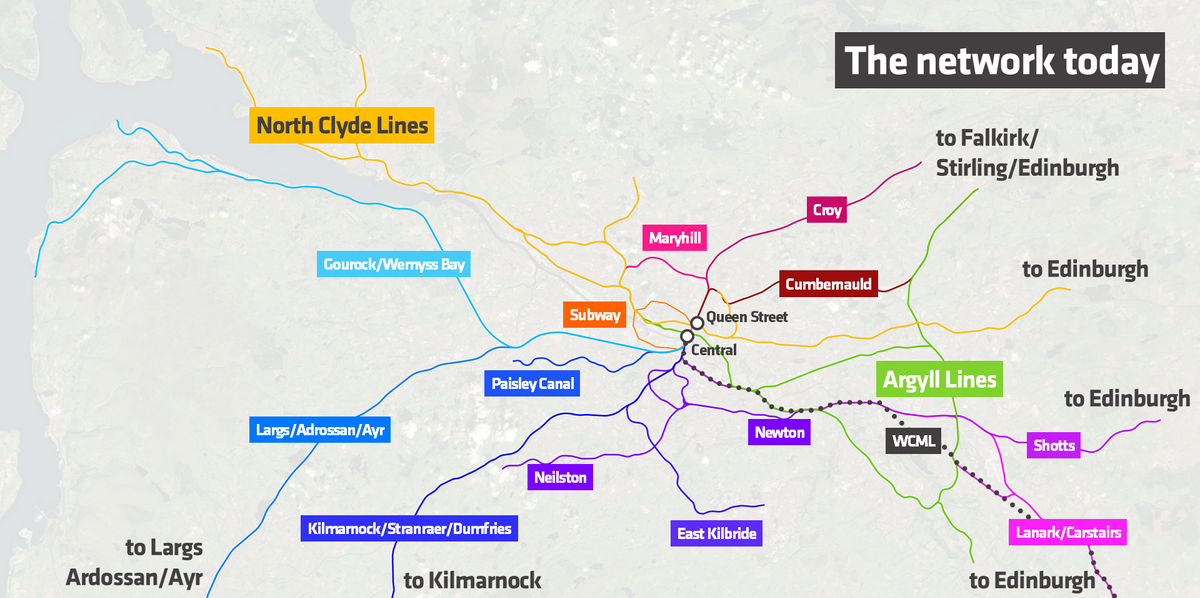

Glasgow’s — and Scotland’s — fragmented infrastructure, often expressed most keenly via transportation networks, is intensely frustrating to him. Take the Clyde Metro.

“It’s great, it’s ambitious, we could build this really coherent urban transport system for the city and almost get to London levels of utility,” he tells me. “Then I look at the East Kilbride rail link, which is connecting the second biggest town in Scotland to the largest city in Scotland. I ask Transport Scotland ‘how’s this fitting in with the Clyde Metro agenda?’”

There’s massive potential for connectivity between the two — it’s a no-brainer, he says, engineer’s hat on. You can dual track them so it’s four trains an hour, like London’s Overground network.

Except you can’t, because Transport Scotland say Clyde Metro is none of their business. It’s a Strathclyde Partnership for Transport project, so they’re not collaborating at all.

“I’m like, ‘right, that’s bonkers,’” Sweeney says, flatly. “And actually infuriating to watch them screw it up. The rail corridor will always be sub-optimal when it could have been a quick win”.

Glasgow, and the wider region, he says, need a “champion”. Some public body — or individual — with a span of control, and the ability to advocate, could overcome such issues.

Sounds like a metro mayor, I venture. Sweeney has previously subtly hinted he would support the creation of such a role, with an op-ed penned for The Glasgow Times last October, headlined ‘Greater Glasgow needs a metro mayor’.

“Utter drivel,” wrote the council’s housing and development convenor, Ruairi Kelly at the time. “Couldn't look more like a job application if he was holding a CV in the picture.”

“I would love to do something like that,” says Sweeney, when I ask if he wants the hypothetical mayoral gig. He’s spoken to Andy Burnham, Greater Manchester’s long standing mayor, about what it entails. It’s not a perfect solution, he adds, but boundary changes have cost Glasgow much of its political heft, including elected representatives in Holyrood and Westminster.

“I think a pool of power in the west [of Scotland] would help us address some of those issues and allow Glasgow to be what it always has: an outward-looking, global city. [We’re] an Atlantic-facing port with a global agenda”. He’s back on architecture to drive the point home: “Glasgow looks like New York or Boston because we had closer relationships with those cities than Edinburgh”.

He’d love to revive shipbuilding here; industrial development is one of his pet causes (although Sweeney has so many of these, he may as well be running an animal shelter). If Labour triumph in the 2026 Holyrood elections — he’s standing again, albeit in a new constituency, currently called Easterhouse and Springburn — he’d lobby for an industry-focused role in Anas Sarwar’s government. He spends a long time detailing how he would have avoided the Ferguson Marine crisis. “I could have fixed that problem,” he says, and when he’s finished outlining his solution (short, mangled version: treat the exercise as Scotland’s re-entry to commercial shipbuilding and support it appropriately, rather than leaving the yard to flail and fail), I actually believe he might have been able to.

As for Kelly’s comments: “Certain people… their jealousies are thinly disguised”. I laugh, surprised at the cattiness, but he’s not done.

“You know, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” he continues, a smirk playing over his lips. “I'm glad that more people are suddenly taking a keen interest in the city’s built heritage”. He’s referencing Kelly taking up the mantle of protecting Glasgow’s old buildings which, to be fair, now falls under housing and development convenor's remit.

“More hands to the pump,” says Sweeney. “There's plenty to go around.”

I dig a little deeper and emerge with the knowledge that he does not get on with the top dogs of Glasgow City Council’s SNP administration: Susan Aitken, Ricky Bell and the aforementioned Ruairi Kelly. “They’ve always assumed bad faith with me,” he says. “Actually, I’m just trying to do the right thing for Glasgow”.

I have to confess that before I met Sweeney, my perceptions too, had been coloured by slight cynicism. I wondered if he would be a media-friendly politician without much substance. But I think he’s actually something else: a devoted disciple of municipal power buoyed along by an almost childlike optimism. Whether this is a positive, depends on the eye of the beholder.

Have you tried to reach out, I ask? Anyone with aspirations of regional oversight has to work with local leaders.

“It’s been very much a firmly closed door,” he says, a touch defensively. “There's been no invitation to come and meet with the council leader, to discuss broader ideas within the city. Even if we might have our occasional grenade throwing in public [...] if you've got an issue, you know, where I am. I'm more than happy to have these issues out. I just want us to find opportunities to work together and build a better city”.

He rubs along well enough with his Labour colleagues, he says, but then I question if he feels isolated.

Sweeney looks surprised and then says: “Yeah, if I’m honest [...] I think on a city level, we could work so much more effectively together with a greater sense of cooperation. I just think there's been so much polarisation since 2014 [when he was a prominent member of the referendum’s No campaign]. It’s like ‘oh, you're just a Unionist, red Tory prick, I'm not gonna work with you’. And I’m not!”

He doesn’t possess much of a private life, he admits. A recent Friday night was spent sitting up until 2am, squinting past the glare of his laptop display to try and plough through all his unanswered emails. And there’s still so much to address: saving a pipe organ, funding applications for the Winter Gardens. He is stretched very thin because his fingers are in so many pies. I suspect his sense of self, for better or for worse, is bound up with the fate of Glasgow, particularly its buildings.

“I feel things personally in a way that’s probably unhealthy,” he confesses. Demolitions are like a punch to the gut. He laughs self-consciously. “Not to sound too bizarre”.

Why?

“I feel robbed,” he says, haltingly. “Robbed of what we could have had”. He is powered, he says, by missionary zeal to try and keep what the city has still got. He sees the planning applications by developers and their assertions about what isn’t feasible to preserve and thinks Glasgow is being taken for a ride. “The city’s been conned, and that’s what really infuriates me. We settle for less than we could get”.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.