In the bowels of a Merchant City pub below Bell Street, LED disco lights spin energetically around an empty dancefloor as a dozen or so men hang about the bar sinking pints. Sam Fender is blasting out of the PA system, a little too loudly. It’s as if the members of a working men’s club have decamped to a dive bar for last orders. Except it’s lunchtime on a Saturday afternoon, and they’re all here because of a Facebook group one of them set up 7,000 miles away.

Ralph Collins, a sixtysomething man with a salt and pepper beard, broad smile and thick black glasses, is dressed smartly in a grey shirt and wool cardigan. In 2012, Collins — people call him Ralfy — created a Facebook group while working on a rig on Sakhalin island.

Ralph started his welder’s apprenticeship at Scotstoun Marine in 1976. Back then, the small yard on South Street employed a little under 5,000 men. Across the river in Govan, over 12,500 were still in employment, albeit precariously. The names of the yards still ring with familiarity: Harland & Wolff, Yarrows, Fairfields — the latter dating back to 1864. Six years earlier, one Sean Connery — then at the height of his Bond pomp — had directed a documentary called The Bowler and the Bunnet, a critical examination of the Fairfield Experiment exploring the problems besetting the Govan yards and the persistent disagreements between management and workers. In the documentary (the first and only film he directed), Connery memorably rides a bicycle around the empty Govan plating shed as he recounts Govan’s demise; a proud community, once at the epicentre of global shipbuilding, peering into the abyss.

“Every boat was the last boat back then,” Ralph says of his early days on the Clyde. Today, it’s a different story. Under the ownership of BAE Systems, the Clyde shipwrights are building advanced warships for the Royal Navy at the former Fairfield yard in Govan, and the former Yarrow yard in Scotstoun. They’re recruiting heavily too. Downstream at Ferguson Marine in Port Glasgow, things aren’t looking so auspicious. The construction of the Glen Rosa, belatedly launched earlier this year, and its sister vessel, the overdue and over-budget Glen Sannox, has been so beleaguered as to place the future of Scotland’s last remaining merchant shipyard in peril. The BBC pondered whether it might be the Clyde’s last traditional ship launch, and the fiasco has its own Wikipedia page. But so long as there’s an appetite for Type 26 Frigates, the future of shipbuilding on the Clyde is warships.

Ralph spent more than three decades in the yards before leaving Glasgow, eventually ending up on a rig on Russia’s Sakhalin Island, north of Japan. Feeling lonely, he decided to create a Facebook group: Shipyard Sayings....funny things heard in the 'yerds'. It had a simple mission statement: “Post funny stories, reunite with old workmates....generally have a laugh”. Twelve years on, he’s back on the Clyde, and the group has 10,400 members and counting.

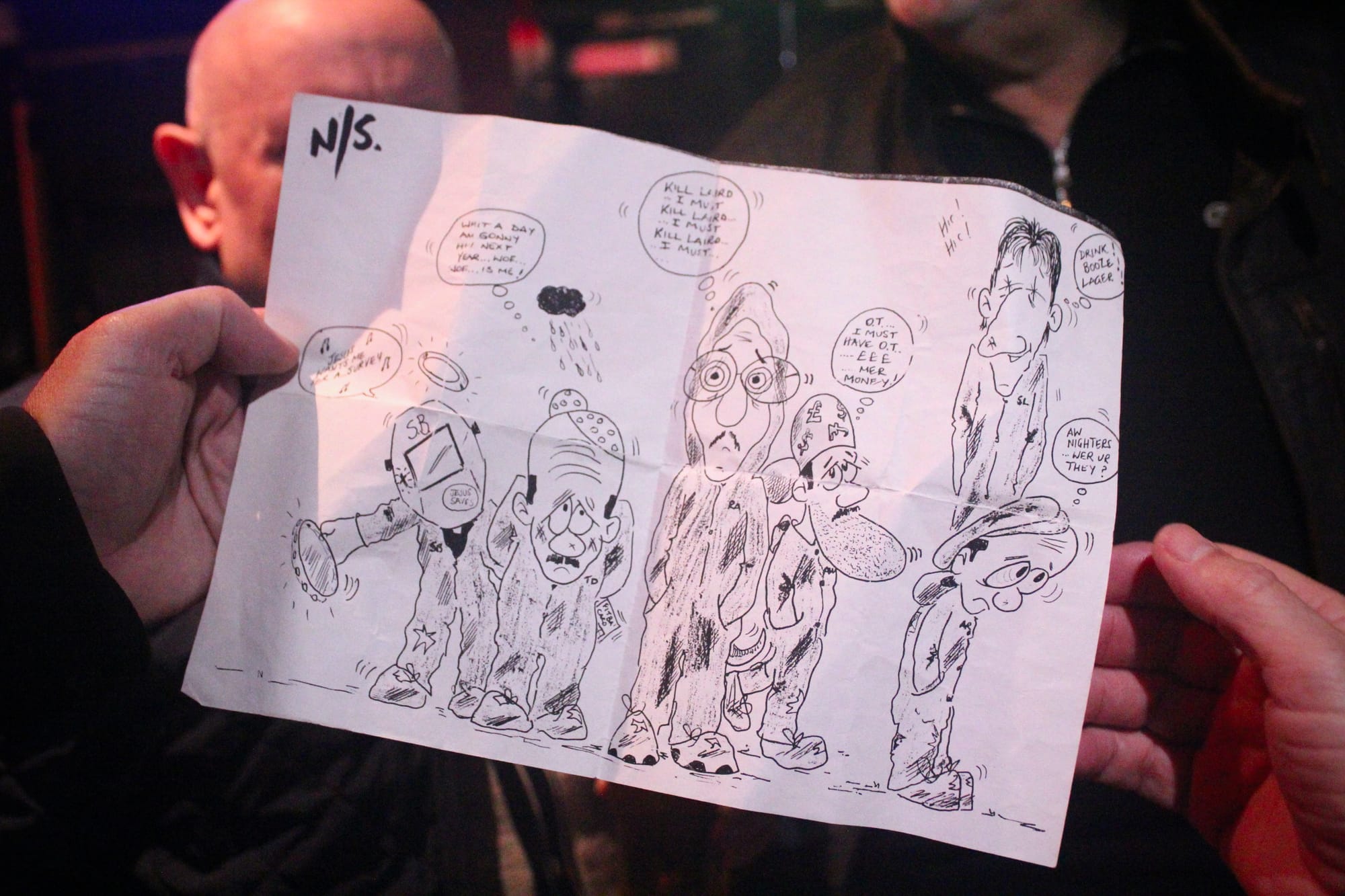

Today is their first ever social: a “shipbuilding day oot” to “meet old comrades and re-live the ‘banter years’”, as the flyer from the Facebook event puts it. At the bar, a crowd huddles around Ralph as he shows off the caricatures he’s drawn of the yards’ well-kent faces. He’s got a talent for it, having authored and illustrated a book — an alphabetised guide to the characters of the upper Clyde, titled Ships, Quips and Cartoons. “My wife didn’t even know I’d written the book. It took me six weeks, a couple of hours a night,” he says.

A debonair man with bright eyes, big shoulders and a bald head comes over to introduce himself. At 38, he’s currently the youngest in the room. His nickname is, unjustly, Fat Boy, but he told me not to tell you that. Like Ralph, he’s a welder by trade. He has worked at the yards since he was 16, when it was still nationalised as Govan Shipbuilding Ltd. “The Clyde is the lifeblood of the city,” he says. “It made all these guys men from boys.”

He explains that “today is a test run to see how we go on”. Next time, they might “go for a biggie”. There are people from shipyards all across the world in the Shipyard Sayings group, he explains, as well as members whose fathers or grandfathers worked in the yards. “People even use the group to find members who may have known their dad,” he says. One woman gathered stories and cherished memories of her father, a plater suffering from dementia.

“Stevie Walker, Super Caulker,” Marty proclaims as a man walks in. “That’s what he calls himself anyway,” Marty quips with a laugh. Almost everyone — apart from Ralph, inexplicably — has nicknames here; Marty has known a guy called Taffy for years but doesn’t know his real name. Taffy is a derogatory term, worse than calling a Scotsman Jock, although nobody says it with any malice, and Taffy doesn’t seem to mind. Then there’s Renzo the Wretch and Critical Cowie. A man called Bert comes over to warn me that when a guy called Gringo comes in, “he’ll chat my ear off so much I’ll need a new notebook”.

A bond through steel

Kenny started at the yards in 1979 as a caulker-burner. These were the “golden years of shipyards”, according to him. “It was full of characters, and everybody kept each other going with funny antics. There was a camaraderie with everyone [… ] I think because you see some workers more than you see your own families throughout the years, you get attached, and people tend to stay in the yards. So it’s a bond, a bond through steel.” It’s the first of many times I hear the word 'camaraderie' over the course of the day.

If you're reading this and you haven't yet joined our mailing list, click here to get Glasgow's new quality newspaper in your inbox every week.

The yards have produced famous funny men such as Billy Connolly and Johnny Beattie. Even Nicholas Parsons cut his comedic teeth in the yards. “Back then, it was pretty hard, so I think we made it easier for each other by making light of things,” Kenny says. “And I think that's why there are so many comedians — the well-known ones — that have come out the yards.” He adds: “There’s people in there that could be on the stage, they're that good. A lot of my friends left to work for the police and things like that, and they all look back on it with almost a romanticism, because a way back then it was a magical place to work.”

Tam went to school with Kenny. His nickname in the yard, he says all too gladly, was Trog, “short for troglodyte”. He’s immaculately dressed because, “Mostly I see these guys at funerals, so I wanted to make a bit of an effort.” He’s wearing a green three-piece wool suit from Slater’s. “That's why I decided to dress up, no? It's a happy occasion.”

Priestly patter

We’re an hour into proceedings. There are around 50 people here now. Knocking back a pint next to a man called Joe the Runner is the stout, short and serious-looking Renzo the Wretch. He’s 60, and one of the oldest serving shipwrights at the social today. “I’ve got my bus pass. They just cannae get rid of me,” he says dryly.

Renzo used to work the night shifts. “They were very cold and very hard. You had to do a lot of welding to keep yourself warm.” Soon after he joined the yard, he saw a man die by falling through a hole in a boat he was working on. “Now it’s more safety-orientated,” he says casually. “Way back in they days, you used to have a drink and drugs culture. You used to be able to go out for a few pints at your break and then come back and enjoy yourself — brand new. You’re not allowed to now.”

Renzo misses those days, “but my stomach disnae,” he says. “I've got a dodgy stomach now from aw the drinking I done when I was younger. I’ve got an ulcer noo. It was a good upbringing, but ye cannae dae that anymair. The only time you see these people noo is at funerals, so this is a good day.” Marty walks over with a cheeky grin. “This guy’s racked up more Sundays than a priest,” he says of Renzo, who has a reputation for working all the overtime the ship gods send. Ralph chirps up: “They say there’s a comedian coming on later, there’s two fucking hundred of them in here!”

Men wi a trade

Marty is working the growing crowd while Ralph holds court, always moving on before long in an effort to speak to everyone in attendance. Willie the Whizz left the yards long ago, and he misses his old comrades. It’s the first time he’s seen Ralph in 30 years. “It’s like it’s only been a week,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve done a week, a month, a year in the yards — you’re made for life. It’s character-building. You should have to do six months’ conscription in the shipyards,” he adds, a bit ominously.

Charlie, a retired pipework manager in a suit and tie, walks over to chat. He pulls out a piece of paper in a protective plastic sleeve, a payslip from May 1961, showing he’d worked 82 hours and 35 minutes in one week. “I was there 46 years, man and boy, never left the place,” he says with pride.

“Over the years, since I left the shipyard, I bump into people now and again in the most bizarre places, but when you see these people, it’s like bumping into family. It’s like not a minute is lost from the last time you've seen them. The craic is the same, the banter is the same, it’s the same memories,” a man called Martin says longingly. “It’s like you're locked into something special that probably doesn’t exist anymore. Everything these days is very sanitised. It was just such a nice place to work.”

The atmosphere at today’s gathering, for all the ecstatic laughter, storytelling and craic, is wistful. Much like on the Shipyard Sayings group, the mood is sentimental and light-hearted. But there is a poignancy too, a yearning for the days of yore, perhaps even of binmenism, the notion that “things were worse, therefore they were better”. This sort of psycho-nostalgic analysis, though, doesn’t quite match the unmistakably optimistic attitude of the day. It’s less Limmy’s Guide to the Clyde (“These were men wi a trade”), and more Billy Connolly’s shipyard jobbies sketch. The mood is celebratory, a collective recollection of simpler times, when men were men and they built things with their bare hands.

The yards, they are a-changin’

Stephen Miller is the third of four generations of his family to work the yards: grandpa, dad and now his daughter too. “Back in the day, shipyards was the only thing we went into, because there were so many — I think 112 shipyards or engineering works on the Clyde,” Stephen says with pride, “From Govan all the way to the Tail o’ the Bank.”

“When I started my apprenticeship, there was only one apprentice that was a woman out of 300 people that started [...] Now we’re bringing women in as platers, welders, engineers. Diversity — brilliant, if you can do the job, you should be able to do it. Gone are the days when women were women, if you know what I mean, and I don’t mean that in a sexist way,” Stephen adds. He mentions a story of the men bringing a sex worker into the yards back in the day, and workers jumping over the wall to break an ankle in order to make a claim. “It’s totally changed for the better, 100%,” he says.

“It’s a good laugh, you hear stories of what it used to be like — it’s changed massively,” his daughter Morgan says. “From when I left school, I never worked with a book, I worked with my hands.” When she was old enough, she asked her dad if she could get a job in the yards, but he told her it wasn’t an appropriate workplace for women.

“In the space of ten years, they’ve adapted to different genders,” Morgan says. After school, she ended up in hairdressing, which she didn’t like, and eventually went back to her dad, who relented. “They’re wanting to make at least 25% of their work squad female, which compared to what it was is phenomenal, considering shipbuilding years ago was mostly a male-dominant workforce,” she adds.

Morgan is here with friend Jodie, who’s been in Govan for five years as an electrician. She’s four years younger, at 22. “The new generation,” Marty comes over to say with a beaming smile. “Aw the guys used to stare in wonder when a lassie walked by,” he says. “Now it’s normal. I’ve been here for 40 years, I know how it works — we need to break the stigma. There used to be a lot of hard drinkers,” he adds. Jodie agrees: “There’s been a major improvement in how women are treated in the past five years,” she says. There’s a trans welder on nightshift, adds Marty. “A lot of the old guys can’t get used to it.”

Morgan says it isn’t hard to be a woman in the yards, but it is different. “You're still trying to find your feet in the place. I wouldn’t say they’re bad to us, I wouldn’t say they’re brilliant, but you’re also treated as one of the guys.”

All three are eager to talk about the legacy of Janet Harvey, one of the very few women who worked as an electrician alongside a 100,000-strong male workforce during the war. Harvey started work at 18 in 1940. Marty says that after the war, she was basically told, “Fuck off, we don’t need you anymore”. She died in 2023, aged 101. A new BAE Systems hall named after her is under construction, large enough to build two Type 26 anti-submarine warships side-by-side. For Jodie, she’s a “hero of modern feminism for the struggle of young women. We need to prove we are here and we are here to stay. She worked for all the war effort; after the men came back, she was disregarded. She was the placeholder to prove we could do it, and we can do it again.”

It’s getting towards the end of the day, and Ralph is feeling elated. “I’m looking at guys here that I haven’t seen for 20 years, but you’d think you had met them yesterday. I’m over the moon. There’s going to be another one in March. I’ve been offered a venue over at the Fairfield Club in Govan. I reckon there’s been 150-plus people today, I think we’ll double that next time,” he says confidently.

Ralph notices a few people he’s not yet spoken to, and he’s off. Later, when he gets home, he posts a message to Shipyard Sayings: “We don’t just build ships, we build people.”

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.