There was a time on the internet when neither YouTube nor Facebook existed. 2003 was the era of MSN messenger chats and Bebo top-16s. Mobile phones were used to play Snake II, send SMS messages at 10p a pop and download silly ringtones. And over the white noise of dial-up internet connections, web developers and amateur enthusiasts published websites using Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) and Flash.

Launched in 1996, Flash was a ground-breaking multimedia software platform that allowed designers to incorporate video, music and animation into their websites. Users no longer had to merely consume content — it was now much easier to create it too. In Glasgow, Flash allowed a new generation of web developers, internet users and animators to spread their wings, code the future, and, in some corners, rip the utter pish out of ned culture.

Some of the most popular websites in the West of Scotland at the time were forums like Hidden Glasgow (still active), the Bloodbus blog (the anonymous author of which would go on to publish a book, then subsequently shut down the blog to juice sales), subcrawl.co.uk (currently inactive but primed for a relaunch) and Limmy.com (which now redirects to Limmy’s Twitch stream), the website of Glaswegian comedian and icon, Brian 'Limmy' Limond. All of these, as it happens, featured in the recommended section of another key site: glasgowsurvival.co.uk.

Glasgow Survival was an early viral phenomenon, its URL etched into the collective memory of many who surfed the web at the time, its games and videos — easily downloadable and endlessly quotable — escaping the bounds of the internet and becoming part of the firmament of 00s popular culture across Scotland. The site featured a basic homepage with sections like: People, Culture, Weapons, Gallery of Neds, and Ned Site Reviews, as well as a forum.

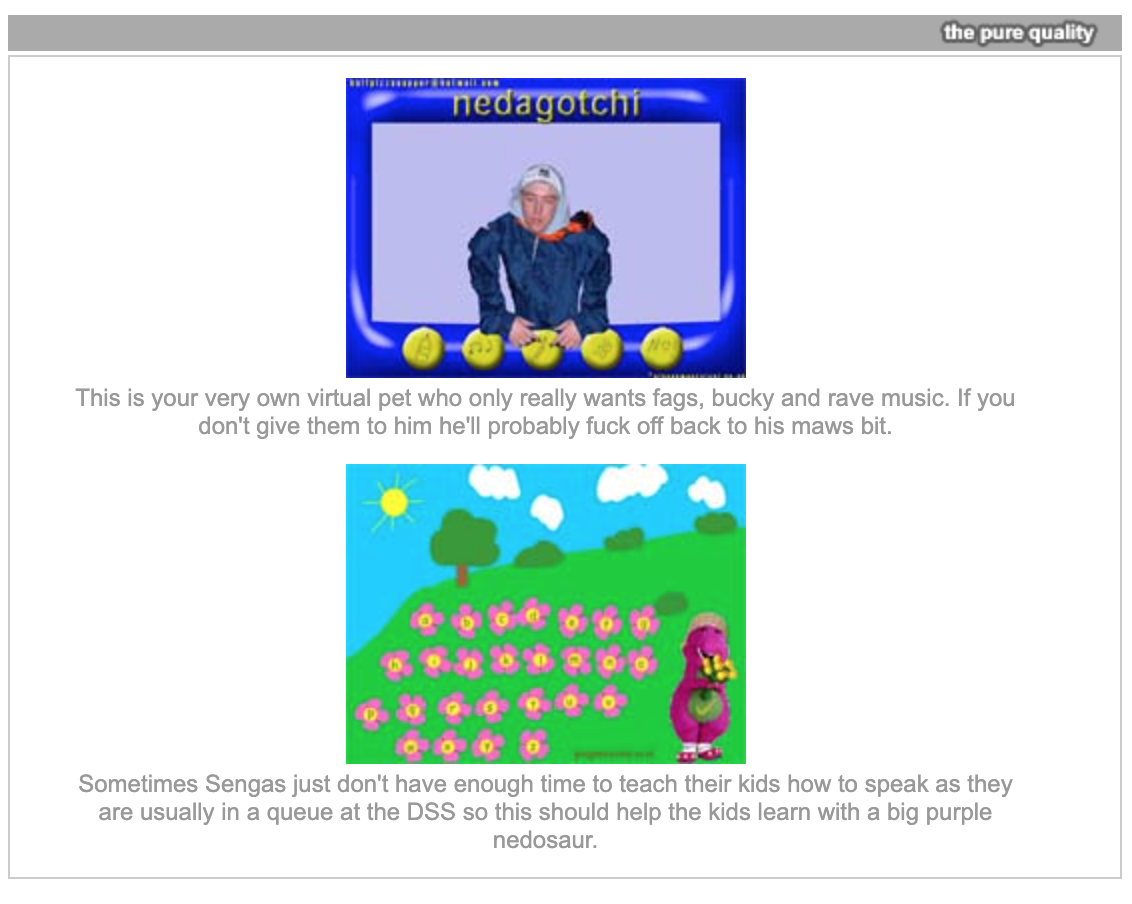

Perhaps the most memorable part of the site was its ‘Toys’ section, which had several Flash games, such as a ‘nedagotchi’ (described as “your very own virtual pet who only really wants fags, bucky and rave music”) and the ‘nedabet’ alphabet keyboard (where ‘a’ was for arsehole, ‘b’ was for bawbag and ‘c’ was for, well…). The Flash-animated videos included ‘Rockin Goth’; a “silent movie set in 20s Glasgow” starring a character called ‘Captain Ned-Hammer’; and the shocking ‘Ned Hanging’, which depicts a ned being hanged by vigilantes. The latter features one of many disclaimers on the website: “Remember, this is just a joke cartoon (albeit in bad taste), and Glasgow Survival does NOT condone the actions performed in it.”

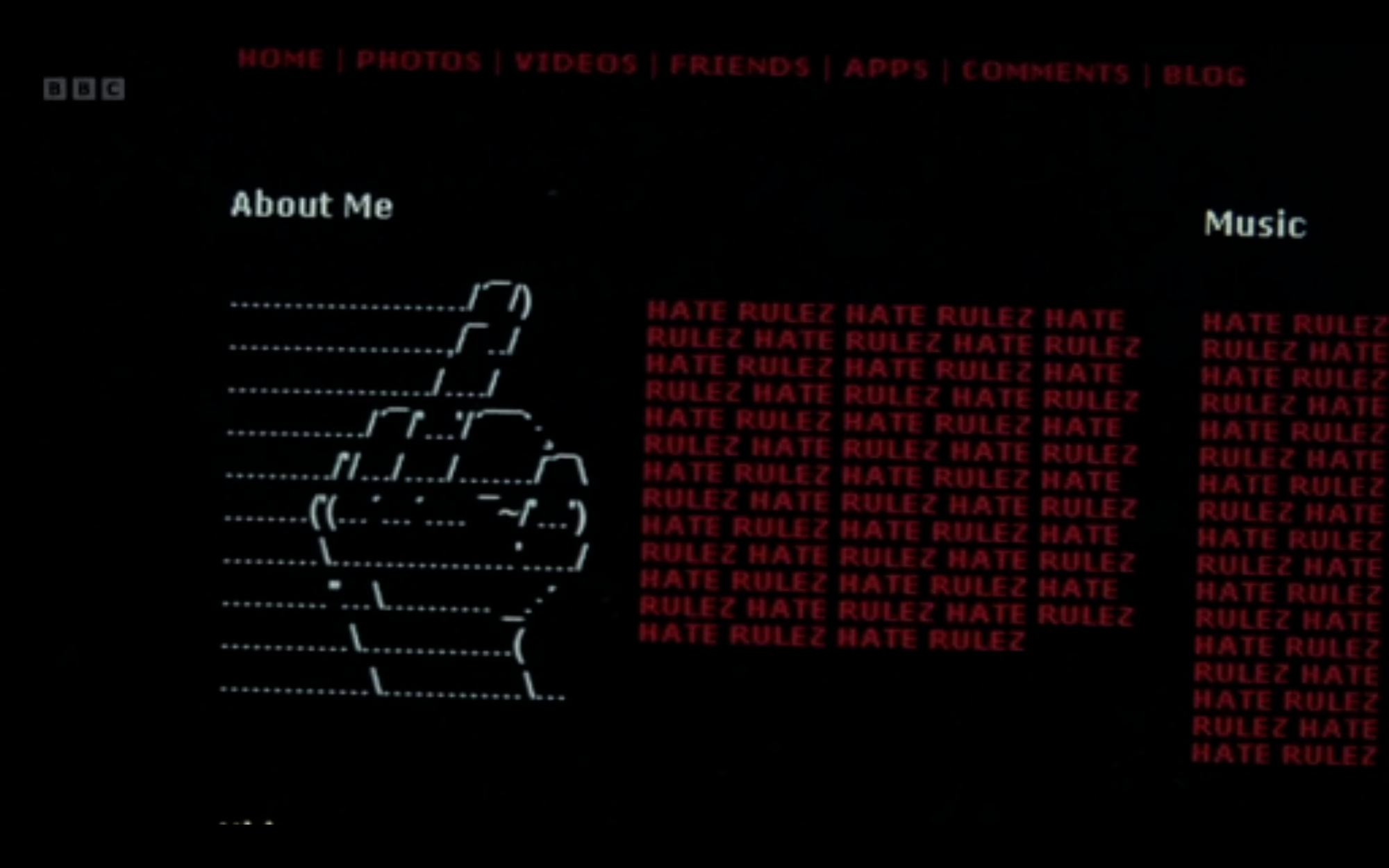

The website was a satire of the old message boards and websites dedicated to young teams from the late 1990s and early 2000s. These sites often contained a homepage and a graphic, normally the name of the young team written in Comic Sans or flashing fluorescent green. Some of these, such as Young Partick Fleeto and Young Posso Fleeto, still exist — you can still browse photo galleries of Lacoste tracksuits, Berghaus Mera Peaks, and Burberry baseball caps, bottles of Buckie and Mad Dog and Frosty Jacks. Glasgow Survival linked to some of these sites on its ‘belters’ section, such as a Kirkintilloch blog called ‘Kirky Stunners’, which described itself as “Oor Luvli Syt Boot How Much The Kirky H8 Lenzie”.

Glasgow Survival is still talked about nostalgically online, resurfacing on forums as people reminisce about the earlier ages of the Scottish internet, share YouTube clips and discuss their favourite games. Today, though, working-class writers, researchers and directors are reappraising ned culture. So what does the demonisation of neds that made Glasgow Survival such a popular and controversial website tell us about the political climate it existed within?

State-sponsored ned warfare

The height of Glasgow Survival’s fame — or infamy — coincided with then-First Minister Jack McConnell’s ‘war on neds’. At the time, there were growing fears around anti-social behaviour, violence (Glasgow was named the “murder capital of Europe” by the World Health Organization in 2005), and so-called ‘benefit scroungers’. The ned became a folk devil for the political classes and tabloids. Glasgow Survival was the satirical website for its time.

To do this sort of journalism, and keep some of it free, we rely on the support of our 370 paying members. To join them, sign up here.

Researcher Gavin Brewis has written extensively about this period as part of his PhD research into “Neds and Ned Culture (circa 1995-2008) through an Oral History of Emotions and Trauma” at Glasgow Caledonian University. He jumps onto Zoom in a black baseball cap and Stone Island jumper, and quickly launches into a fluid class analysis of the Nineties and Noughties nedosphere. Brewis believes there was an “engineering of a new underclass” across the UK at the time: neds in Scotland, chavs down south. “It was all part of an anti-poverty rhetoric,” he says, which allowed the New Labour government to push through new laws like the Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003 in England, and 2004 in Scotland.

“Morality,” Brewis believes, allowed New Labour to “create and repurpose a dangerous class, the wrong type of working class”, thus dividing the working class into “right types and wrong types”. He’s received online abuse for his research, both after an STV interview and following publications on the topic for the D.Rad Project and Interregnum. The latter, in particular, led to a vitriolic response on the r/glasgow subreddit, where many users recalled being battered by neds growing up. Some argued Brewis was conflating what they saw as a justified demonisation of violent neds with a wider demonisation of the working classes.

“I can understand why some people might have a pop and even be angry at me for trying to give these people a voice, a fucking position in history,” he says. “Because they were part of history, even if it was a negative part. There’s a lot of positives in there as well, which are totally dismissed. The same people who were talking about systemic violence and oppression against the working class for generations forgot all that stuff when it came to neds.”

A major part of the problem, he thinks, concerns our inability to conceive of neds as both “victim and perpetrator — when we should, because that’s nuance”. He believes many people at the time bought into narratives that served the ruling classes. “The people who are benefiting from scapegoating the youth, it's not even the people who are creating these websites. It's those above them. It's the people in power.”

Then again, some of the people Brewis interviewed for his PhD liked the website. “Some of them said: ‘Well, actually, we quite liked the representation which we seen in there. We thought it was quite funny, because, well, we are just wee arseholes. We were just fucking wee cunts who were causing problems for people.’”

Glasgow Survival revival

Five years ago, a user on the r/glasgow subreddit called @daleloudon posted a screengrab of Glasgow Survival from the Internet Archive, and wrote that he recalled seeing somewhere that Limmy was behind the site — although he also admitted he had “no evidence to prove it, so could be a load of shite”. Several more users gave their piece, with one remarking, “The ned in yellow [in the Rockin’ Goth video] definitely sounds like him, so you could be onto something”. A now-deleted user commented that he wouldn't be surprised if it was Limmy, given his track record making Glasgow-themed Flash animations. “Ned in yellow does sound like him,” he wrote in agreement.

If you're reading this and you haven't yet joined our free mailing list, click here to get the Glasgow Bell in your inbox every week.

We contacted Limmy for this article, but he declined an interview and didn’t respond to our questions. We also got a bounceback from the original Glasgow Survival email address, and received no response from the email inbox of the creator of the Nedagotchi game, which appears to have been submitted to the site. Limmy’s own website, limmy.com, was recommended on Glasgow Survival as, “The original and best site for glasgow based playthings and basic limmyness”. It would therefore be a bold move if Limmy was indeed behind it — the Glasgow Survival email inbox regularly received threats of violence, which the site’s moderator would gleefully republish on ‘the pure news’ sidebar section.

The question, then, is who else in the city had the necessary web developing and Flash animation skills, not to mention the blackest of humour, the flair to record voiceovers, and a taste for the controversial?

‘The main Flash cunt in there’

In Limmy’s autobiography, he talks about how he got his start as a web developer, and how a game-changing multimedia application “changed my fucking life”. It was around 1998, he’d not long turned 24, and had got a start on a New Deal course while unemployed, after graduating in multimedia technology from Glasgow Caledonian University in 1996. “I’d made some basic websites, I did some Photoshop stuff, general all-rounder things,” he writes. That was until he discovered Macromedia Flash 3, which “let you do all these animations, these big, full-screen animations, things that looked like videos or cartoons or arty title sequences, with sounds and music and everything”.

Limmy quickly taught himself how to use Flash, and impressed the high heid yins at Black ID, a company based on Speirs Wharf where he was working as a website designer. By early 1999, he was the “main Flash cunt in there”. He left Black to start Flammable Jam with Donnie Kerrigan and Michael Falconer, and in 2001 co-founded Chunk Ideas (also with Kerrigan, who continues to run the company today). Limmy’s Flash work from this period included games like Snowball, in which the player has to hit a window of a Glasgow tenement with a snowball, as Limmy’s voiceover shouts fucking heeeeere”. When you hit a window, a gruff voiceover (also Limmy) shouts “here, cunto” in response. While the graphics are a lot more advanced — this was a professional media-marketing company, after all — it feels like a grown-up cousin of the ‘Toys’ section on Glasgow Survival.

Limmy also made short Flash videos like Glaswegian Halloween, which is still on his YouTube. He told the Guardian in 2007 that he eventually used his Flash skills to build limmy.com, as somewhere to put his “wee animations, wee interactive toys” (like the swearing xylophone, which can thankfully still be viewed, and indeed played, online here). By 2002, he was uploading videos, skits and comedy shorts, and in 2006 he sold his stake in Chunk to co-founder Donnie Kerrigan to focus on his comedy career.

In late 2006, Limmy launched the World of Glasgow podcast, receiving interest from the mainstream press and media. Though the podcast was eventually removed (some of the characters had not aged well), in June 2009, the BBC commissioned series one of Limmy’s Show, first airing in 2010. Several podcast characters evolved into key protagonists of the show: John Paul, a young ned hell-bent on terror and humiliation, is a distillation of the sort of neds Glasgow Survival had satirised, stereotyped and goaded five years before. In series one, episode four, we see Limmy sitting at his desk, shaking his head in disapproval. He points at his computer screen, and the camera shifts to show him looking at John Paul’s website. It’s an HTML affair, text-heavy, with a happy hardcore soundtrack and videos of JP gloating about heinous acts he’s inflicted on others. At the end of the episode the credits roll, notifying the viewer that the episode was written, animated and directed by Brian Limond.

Fans of Limmy know ned culture features prominently in his comedy, but this is true of many comedians from the Nineties and Noughties. Ned pisstakes featured heavily in BBC Scotland’s Chewin’ the Fat, such as the interpreting for the neds and ‘Teuchters versus neds’ sketches. Chewin’ the Fat’s official BBC website, à la Glasgow Survival, even had a ‘neds’ section, dated October 2014, with ‘Ned Olympics’ games such as taxin’ trollies and tannin’ windaes, ned language lessons, AKA ‘neducation’, a ned personality test, and the glaikit chef’s ‘cooking wi neds’ recipe guide.

Comedian Neil Bratchpiece also gained early internet fame with the release of ‘Here You (That'll Be Right)’ by NEDS Kru ft. The Wee Man in 2007. The music video features a young Bratchpiece as the ‘Wee Man’ with a notable fake facial scar, cutting about town in a tracksuit, Burberry hat and gold chain, novelty-sized spliff and bottle of Bucky in hand, rapping about locking up yer grannies, pumping yer maw and ripping open folks jaws. It launched the career of the young Scottish comedian, and has some five million views on YouTube.

While Limmy might have had the right skillset, as well as having been involved with leading digital design agencies in the city at the time, boiled down, the Reddit rumour remains little more than an unfounded theory. The anonymous creator of one of Glasgow’s most celebrated and notorious websites remains a mystery — for now, at least.

Nedworld revisited

Gavin Brewis enjoys the comedic representation of neds in BBC Scotland shows like Chewin’ the Fat and Still Game, but doesn’t feel the same about Glasgow Survival. “There was a nastiness to it, and it was punching down on poverty.” Brewis is part of a cohort working to reappraise and contextualise ned culture and the demonisation of working-class young people during the Nineties and Noughties. While he does so in an academic context, writers like Graeme Armstrong do so in a literary one — the latter following in the footsteps of Irvine Welsh by writing in a modern Scots vernacular. In 2020, Armstrong published his debut novel, The Young Team, following a young man called Azzy as he negotiates life in a gang growing up in the West of Scotland. Subsequently, he made a series on street gangs for BBC Scotland to “understand why young people are seduced by the perceived glamour and excitement of gangs”. The series features an interview with actor and director Peter Mullen, who wrote and directed the acclaimed 2010 film NEDS.

‘Ned’ was first added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2001. Various theories for its origin have been posited over the years, from a derivative of the Edwardian-era Teddy Boys, the first youth movement of post-war Britain, to Percy Sillitoe, who served as chief constable of Glasgow police in the 1930s, and wrote about neds in his 1955 book ‘Cloak Without Dagger’. Others believe it may go back as far as the 19th century, to Australian outlaw Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly. Either way, its origins are similar to derogatory and racist terms like hooligan (an Irish slur based on the name Hoolachan) and chav (a word of Romani origin). Brewis, for his part, claims he’s cracked its etymology once and for all — but hastens to add, with a wry smile, that we’ll have to wait until his thesis is published to find out what it is. Whatever its precise origins, the word casts a long shadow: two decades after its inclusion in the dictionary, the council leader Susan Aitken appeared to blame graffiti problems in the city on “wee ned[s] with a spray can”.

Brewis pulls out two books, Nedworld (with a Burberry pram on the front cover) and Chav!: A User's Guide to Britain's New Ruling Class, from his bookshelf. Both, along with Glasgow Survival, are good examples of an othering not only of ned culture, but working-class young people more generally. Reflecting on the Rockin Goth video, Brewis remembers watching it 20 years ago and finding it funny, even laughing at it. Looking back on it, though, he sees it as “fucking depressing, fucking grim”.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.